Defined benefit funding code consultation document

This consultation document forms part of the defined benefit funding code consultation.

Save this page as a PDF

On this page

- Introduction

- The funding regime

- Long term planning

- Applying this in practice

- Systemic risk considerations

- Appendix: Consultation questions

Introduction

The government’s 2018 white paper Protecting defined benefit pension schemes announced a package of measures to improve the security and sustainability of defined benefit (DB) scheme funding.

These measures, which look to embed existing good practice, are being implemented through a package of primary and secondary legislation, a revised DB funding code, and updating relevant guidance.

This is the second of two consultations on the revised DB funding code. Since 2018, we have run an extensive consultation and engagement programme to ensure key stakeholders have the opportunity to add their views and to allow sufficient time to develop proposals. We will continue this approach until the revised code is finalised.

The DWP published their draft regulations in July 2022 and are in the process of considering the responses received during the consultation period. We will continue to engage closely with DWP and industry after this consultation as we finalise the code and to take account of changes made by DWP in response to their consultation.

First DB funding consultation on the funding framework

Published in March 2020, our first consultation (National Archives) set out our initial proposals for a clearer, more readily enforceable funding framework. We framed our proposals within the policy intent set out in the Government’s 2018 White Paper as the Pension Schemes Bill was going through Parliament in parallel.

In our first consultation, we welcomed comments on all aspects of our consultation proposals, particularly:

- our proposed regulatory approach (twin-track valuation submission route)

- the key principles that should underpin all valuations

- options for how these principles could be applied in practice through more detailed guidelines

We were pleased with the number of responses to our first consultation – 127 – and the level of engagement throughout the process. The responses provided many good challenges and ideas, with a wide range of views from different areas of the pensions industry.

We published an interim consultation response in January 2021. You can now read our full consultation response (National Archives) published alongside this document.

Our second consultation on the draft DB funding code of practice (code)

We are now seeking views on a draft DB funding code of practice, which provides practical guidance on how trustees can comply with scheme funding and investment requirements.

The draft code provides an overview of the funding regime. Each chapter then sets out our expectations considering the legislative requirements.

The draft code is split into three parts:

- Overview of the funding regime

- Long-term planning

- Application

We have developed this draft code to reflect the direction of legislation as was consulted on by the DWP from July to October 2022, responses to our first consultation and our additional analysis.

We have drafted this consultation document in a way that explains our approach and includes relevant considerations and obligations, along with consultation questions for each chapter of the code (except the introduction chapter).

In some areas, we have kept this explanation brief whereas, in others, we have included more, reflecting the more complex nature of the issues.

We have not repeated all the code’s text drafting here, so this document should be read alongside the code itself.

In parallel to this consultation, we are also consulting on our regulatory approach, including our approach to developing a Fast Track regime.

Timetable and further engagement

The Pension Schemes Act 2021 received Royal Assent in February 2021. However, the funding clauses of the act will not come into force until the Occupational Pension Schemes (Funding and Investment Strategy and Amendment) Regulations 2023 (the FIS regulations) are also brought into force.

We expect the earliest the final regulations and code to come into force together will be 1 October 2023. To meet this timescale, given the legislative process, we aim to lay the final code before Parliament in mid-June alongside the final regulations. The Secretary of State, if the code is approved, must lay the code before Parliament for 40 days.[1]

We have developed the draft code to reflect the draft regulations. We recognise that the final form of the regulations are not yet known and may change following the DWP’s consultation. We are publishing this consultation before the regulations are finalised to help the industry reach a more complete view of how the regulations may be interpreted and implemented. Any changes that are made to the final regulations when they are laid in Parliament will need to be reflected in our final code. We will discuss this with the industry throughout this process.

The current timetable is subject to change.

Footnote for this section

- [1] Section 91 Pensions Act 2004

Who is this consultation for?

We would like to hear from any interested party, in particular trustees, employers, advisers and members of DB pension schemes and their representative organisations.

Closing date

This consultation document was published on 16 December 2022 and will run for 14 weeks. The closing date for responses is 24 March 2023.

Responding to the consultation

We encourage you to respond to the consultation using the online response form.

Read our consultation questions.

Alternatively, you can post your response to:

DB funding code team

Regulatory Policy

Advice and Analysis Directorate

The Pensions Regulator

Napier House

Trafalgar Place

Brighton

BN1 4DW.

If you would like to submit supplementary materials electronically, please note they will be subject to a 25MB limit (therefore, please send any larger documents in batches). If you have any queries about this consultation, please email DB.Consultation@tpr.gov.uk.

We will be holding a series of engagement sessions throughout the consultation period as another format for providing your views.

When responding, please advise whether you are responding as an individual or on behalf of an organisation – and if the latter, which organisation.

We may need to share the feedback you send us within our own organisation or with other government bodies. We may publish this feedback as part of our consultation response.

If you want your comments to remain anonymous or confidential, please state this explicitly in your response.

However, please be aware that, should we receive a formal request under the Freedom of Information Act, we may be required to make your response available.

Government consultation principles

This consultation follows the government’s consultation principles, which state that consultations should:

- be clear and concise

- have a purpose

- be informative

- be only part of a process of engagement

- last for a proportionate amount of time

- be targeted

- take account of the groups being consulted

- be agreed before publication

- facilitate scrutiny

The funding regime

Code chapter 2 - An outline of the funding regime

This chapter of the code provides an outline of the DB funding regime and the new draft requirements proposed in the DWP FIS regulations.

In this section, we cover what the requirements include at a high level. Our overview is not meant to replace the process of trustees and advisors reviewing the FIS regulations and forming their own opinions. It acts as a short summary and guide to help readers better understand the regulations and set the context for the code.

Along with this summary, we have included our views on how we see the Funding and Investment Strategy (FIS), Statement of Strategy (SoS) and scheme valuations interacting together.

We are encouraging trustees to consider all these elements together and would expect this to be done at least every three years alongside the valuation, unless trustees are required to review the FIS sooner for one of the reasons set out in the FIS regulations.

The scheme’s Technical Provisions (TPs) must be set consistently with the low dependency funding basis which in turn must be set in relation to the low dependency investment allocation. So, we have set out that trustees must do this.

The TPs must also be set consistent with the journey plan.

The funding and investment strategy regulations do not amend the trustees’ duties in respect of investment decisions – they just set out the requirements for a plan to be in place for this. However, we expect that trustee’s investment strategies will in practice be broadly consistent with those set out in the funding and investment strategy. This does not mean they should be identical at all points, as there may be good reasons for some divergence. However, to fulfil the policy intent, we expect the trustees’ investment decision to broadly follow those set out in their funding and investment strategy.

Consultation question:

- Are there any areas of the summary you disagree with or would like more/less detail? If yes, what areas and why?

Long term planning

Code chapter 3 – Low dependency investment allocation

Policy intent

The funding and investment strategy regulations introduced the requirement for a scheme to plan to be in a position of low dependency by the time they are significantly mature. Being in a position of low dependency is set out by the DWP as being a position whereby “…under reasonably foreseeable circumstances, the scheme is not expected to need further employer contributions....[2]”

This is the guiding aim, but there are principles sitting behind this to meet this as described in the introduction section of the code.

We do not believe that the requirements intend that the scheme should eliminate all risk or expect schemes to be funded in a position that would insulate them from the possible need for additional contributions from an employer. Indeed, the DWP’s consultation document is clear that it is only ’reasonably foreseeable’ circumstances that the scheme should be protected against.

Footnote for this section

- [2] DWP consultation on the draft regulations, July 2022, paragraph 3.11.

Broadly matched

The legislation requires that for the low dependency investment “the assets of the scheme are invested in such a way that the cash flow from the investments is broadly matched with the payment of pensions and other benefits under the scheme”

‘Cash flow matching’ is an approach which allows schemes to hold assets whose expected cash flows to the scheme mirror those of the schemes expected benefit and expense payments. This gives the trustees confidence that the assets they hold will be able to pay the benefits and expenses as they fall due.

We have set out in the code an explanation of how we think trustees should approach this principle. This includes two main aspects:

- the nature of the assets that we think are acceptable for cashflow matching purposes

- what we think it means for cash flows to be ‘broadly’ matched

Matching assets

The key characteristic for an asset to be a matching asset is that it contains a contractual obligation for known amounts of cash flow to be paid to the scheme at certain points in the future. However, assets with contractual obligations vary in terms of how risky the underlying payments are.

The asset classes that trustees typically use to build cashflow matching portfolios include, government bonds, investment grade credit, alternative credit and a range of secure income investments including, for example, some property and infrastructure related investments. Interest and inflation rate derivatives may also be used to better match the profile of the investment cash flows with the profile of the expected scheme outgo.

We do not intend in the code to limit the assets that can be considered for cash flow matching purposes. We think it is reasonable for schemes to consider a wide range of investment opportunities that may have suitable characteristics for matching expected cash flows. We would expect that credit investments would be heavily weighted towards investment grade but recognise that some sub-investment grade investments may usefully contribute to meet scheme outgo.

It is also important that trustees understand the risks associated with the liability side of the equation and understand the risks from actual scheme outgo differing from expected scheme outgo. For example, higher or lower number of members taking early retirement or tax-free cash lump sum on retirement might accelerate or delay benefit outgo whilst the impact of higher or lower levels of mortality will lead to lower of higher cash outgo than expected. Changes in the benefit outgo profile over time will impact on the need to adjust the assumed asset portfolio to maintain a cash flow matching approach.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with the principles for defining a matching asset that i) the income and capital payments are stable and predictable; and ii) they provide either fixed cash flows or cash flows linked to inflationary indices? If not, why not and what do you think is a more appropriate definition?

Broadly matched

Cash flow matching can be implemented with different levels of accuracy, sensitivity, and liquidity. The legislation does not require the low dependency investment allocation to assume full cash flow matching for the purpose of the low dependency investment allocation, though some schemes may choose to do so. The approach trustees adopt for their individual scheme in relation to their low dependency investment allocation will be based on their future objectives for the scheme and the time horizon over which they intend to manage the scheme. For example, a scheme that is targeting buy-out in the short term is likely to focus on cashflow matching assets that are liquid; whereas a scheme that is unlikely to buy-out may have an increased focussed on less liquid cash flow matching assets.

Some schemes may plan for a phased approach to cash flow matching, where they will seek to accurately cash flow match the short to medium term cash flows and then broadly match longer term cash flows but look to improve the matching of the liability profile on an ongoing basis.

A partially matched cash flow portfolio only provides a degree of liability hedging. We set out in the code that where a scheme plans for partial cash flow matching, it is important that they plan for mitigations for interest rate and inflation risks over the longer term in their low dependency investment allocation. Interest rate and inflation hedging would allow the scheme to hedge against changes in long-term interest rates and inflation and be better positioned to purchase cash flow matching assets at points in the future in line with their liability profile.

The ’yield curve’ describes the rate of interest available at different terms in the future and in markets like the UK, there is a real interest curve as well as a nominal interest curve. The difference between these curves shows the inflation that is priced in. If the evolution of interest rates or inflation pricing changes by different amounts in the future, the shape of the yield curve can change whilst the average long-term interest rate or inflation pricing is unchanged. This could mean that a scheme may have hedged their interest rate / inflation risk from a parallel movement but still have an asset / liability mismatch rate risk from an adverse movement in the yield curve.

Therefore, it is important that a scheme’s plans for their low dependency investment allocation includes hedging against the shape of the interest rate yield curve or inflation yield curve rather than just the average duration of the liabilities only.

To achieve this, we set out in the code it would be acceptable in the low dependency investment allocation to ’bucket’ cash flows from the scheme by aggregating the expected cash flows of the scheme over, for example, short, medium and long durations or by defined periods. These expected aggregated liability cashflows can then be broadly matched with the expected asset cash flows from the low dependency investment allocation. Some schemes will want to plan do more than this, but this approach would be regarded as an acceptable minimum.

We therefore believe an approach where the scheme plans for some cash flow matching for a portion of their liabilities combined with high levels of hedging for interest rate and inflation consistent with the duration of their liabilities – including differing points along the yield curve - would be sufficient to be deemed broadly cash flow matched. There may be other approaches to broad cash flow matching which are also plausible.

Our expectation in the code is that being broadly matched for the low dependency investment allocation, is that this requires a minimum level of interest rate and inflation hedging of at least 90%. In other words, when looking at the level of resilience the value of the assets should be at least 90% sensitive to the interest rate and inflation risk of the liabilities on a low dependency basis at point of significant maturity. If there is more than 10% held in growth assets, this would mean that the matching assets require leverage and/or the duration of the matching assets to be longer than that of the liabilities.

We recognise in the code that we expect the level of accuracy to be proportionate to the size of the scheme and governance arrangements.

Consultation questions:

- Do you agree with our approach for defining broad cash flow matching? If not, why not and what would you prefer?

- Do you think draft adequately describes the process of assessing cashflow matching ? What else would be appropriate to include in the code on this aspect?

- Should the code set out a list of the categories of investments into which assets can be grouped for the purposes of the funding and investment strategy? If so, what would you suggest as being appropriate?

- Do you agree that 90% is a reasonable benchmark for the sensitivity of the assets to the interest rate and inflation risk of the liabilities?

- Should we, and how would we, make this approach to broad cash flow matching more proportionate to different scheme circumstances (eg large vs small)?

Approach to assessing resilience

The legislative requirement for the low dependency investment allocation is that “the assets of the scheme are invested in such a way that the value of the assets relative to the value of the scheme’s liabilities is highly resilient to short term adverse changes in market conditions”

In assessing the extent to which their low dependency investment allocation is resilient, trustees should consider how the value of assets and liabilities would perform under short term adverse changes in market conditions.

In our first consultation we discussed different approaches to measuring investment risk – including defining a percentage of growth assets or using a stress test. There was broad support for use of a stress test.

We believe that the use of a stress test for a scheme’s low dependency investment allocation is best placed to enable trustees to satisfy the high resilience requirements set out in the DWPs draft regulations. We have set out in the code that we expect trustees to take this approach looking at both the matching assets and non-matching (growth assets).

The preferred approach from respondents to our first consultation was to base the stress test on the Pension Protection Fund’s (PPF) stress test factors since it was already used by many schemes. We propose to use this approach as the stress test for Fast Track in relation to testing against this principle.

However, to enable schemes to better reflect their own circumstances or make use of analytical tools they already have, we have set out in the code that schemes should carry out their own one year, 1-in-6 Value at Risk (VaR) or stress calculation (which is consistent with the strength of the PPF stress test factors).

Trustees may already use alternative risk measures such as one year 1-in-20, VaR or more sophisticated approaches. We do not want to discourage trustees from these approaches but want to set out a benchmark for the minimum level of stress test we expect to see.

We also set out in the code that we expect trustees to consider other forms of analysis to understand the resilience of their low dependency investment allocation portfolio. For example, in relation to the cashflow matching assets, trustees should consider how the cashflows that would be generated are likely to perform compared to the expected scheme outgo under a range of different stresses and scenarios. It is also important to undertake scenario analysis of the benefit outgo to see the extent that cashflows might diverge against a central scenario.

Again, for proportionality, the benefits of such an exercise should be weighed against the cost.

Setting a maximum stress

While the ‘broadly matched principle’ is likely to mean that the scheme will plan for the purposes of the low dependency investment allocation significant levels of matching assets and interest and inflation rate hedging, they may still plan for a reasonable level of investment in non-matching (growth) assets.

Trustees may plan to hold growth assets for a range of reasons, including in the expectation of building up additional surplus over time to fund unexpected liabilities such as increases in life expectancy or expenses and increasing the funding level to enable buy-out. The asset-liability modelling produced by Government Actuary’s Department (GAD) as discussed in our first consultation illustrated that funding outcomes can be improved by holding some growth assets.

However, there is a limit to the overall level of growth assets that can be included for a portfolio to still meet the principles of a low dependency investment allocation since such assets add risk to the portfolio. The income from equities (for example) is not guaranteed and can go up or down. At times it will also be necessary to sell growth assets to (for example) meet future benefit payments, purchase matching assets or respond to collateral calls and the price at which growth assets can be sold is unknown and volatile. This could lead to forced selling at lower than expected prices which could be insufficient for the needs of the scheme.

As discussed in our first consultation, we modelled differing investment strategies for a schemes at significant maturity, including strategies that held around 20% to 30% in growth assets. The GAD modelled these scenarios which we used to illustrate the likelihood for a scheme achieving Buy Out and the estimated cashflows remaining unpaid for those schemes that did not reach Buy Out. Based on the modelling results and our understanding of the policy intent, we believe such levels of growth assets in a scheme’s low dependency investment allocation could be consistent with the DWP’s draft regulations.

When trustees plan for a material holding in growth assets, the only way to match the full cash flow profile of the liabilities is by either the use of leverage or increasing the duration of the matching bonds to be greater than the duration of the liabilities.

In order to plan to match the duration of the assets to the liabilities and limit the impacts of the 1-in-6 stress, planned portfolios with over 20% - 30% in growth are likely to need some form of leveraged liability driven investment to achieve this. Limiting growth assets to below 20% of the overall planned portfolio means that the portfolio would be able to better match duration without use of leverage, or through minimal levels of leverage required in matching assets.

Using the PPF stress factors and based on an average duration of 20 years for the gilt portfolio and 8 years for the corporate bond portfolio, we have modelled the following investment strategies at duration 12 years (ie point of significant maturity). These show growth assets in the 25% to 30% range with various matching assets to achieve the necessary levels of hedging (ie around 90%) and that the maximum stress associated with these strategies is around 4.5%.

Table showing example strategies and stresses

| Strategy 1 | Strategy 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Equities | 25.0% | 30.0% |

| Corporate bonds | 35.0% | 24.5% |

| Gov / IL Bonds | 40.0% | 45.5% |

| Duration assets | 10.8 years | 11.1 years |

| 1-in-6 VaR | 4.4% | 4.6% |

We recognise these estimates are approximate and schemes may be able to achieve better risk reduction or matching. We also recognise, as we discuss in the Fast Track section, that there is no perfect answer to what low dependency means in practice. However, we believe that a maximum stress of up to 4.5% would allow for portfolios to have between 25 to 30% in growth assets, depending on their liability hedging approach, alongside sufficient matching assets to be compliant with the legislation. We believe this is likely to be at the outer edge of compliance with the intent and principles in the regulations and have set out in the code the expectation that a schemes low dependency investment allocation portfolio is within the 4.5% maximum stress based on a one year, 1-in-6.

Consultation questions:

- Do you agree with our approach that a stress test is the most reasonable way to assess high resilience?

- Do you agree that setting the limit of a 4.5% maximum stress based on a one year 1-in-6 approach is reasonable? If not, why not and what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree that we should not set specifications for the stress test but leave this to trustees to justify their approach? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

Liquidity and proportionality

We have not set out detailed expectations in relation to liquidity. Since the low dependency investment allocation is a scheme’s planned portfolio, it is unlikely to be proportionate for the trustees to carry out a detailed assessment here. Liquidity issues for the investments actually held by the scheme are set out later the code.

We also set out that we expect trustees to take a proportionate approach to the level of detail required for the low dependency investment allocation. For example, schemes that have a long period of time before they reach their relevant date low dependency investment allocation can take a more approximate approach towards their plan for the low dependency investment allocation. More granularity is expected as schemes get nearer to their relevant date.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with our approach for not expecting a detailed assessment of liquidity for the low dependency investment allocation (LDIA) since we have set out detailed expectations in relation to schemes’ actual asset portfolios?

Code chapter 4 - Low dependency funding basis

The regulations set out that a low dependency funding basis must use actuarial assumptions, which are set on the following presumptions:

- The scheme’s assets are invested in accordance with ‘the low dependency investment allocation’.

- The scheme is already fully funded on a low dependency basis.

If so, it is expected that no further employer contributions would be required under reasonably foreseeable circumstances.

We do not intend to take a prescriptive approach relating to the actuarial assumptions for the low dependency funding basis. We believe this is best left at the level of principle, given the scheme-specific nature of many of the assumptions needed for an actuarial valuation.

We do not think it practical or expected that trustees need to stochastically model each assumption or set of assumptions in order to demonstrate the principle that ’no further employer contributions are expected to be required to make provision for accrued rights’ would be met under reasonably foreseeable circumstances.

Rather, we believe that it is sufficient to have a prudent and evidence-based approach to setting the assumptions in line with the scheme being fully funded on a low dependent investment allocation, combined with a check that the overall level of prudence across the assumptions is appropriate.

Ensuring that the assumptions are chosen prudently will mean that the funding basis does not undermine the guiding principle of low dependency. We recognise that trustees may choose to include a high level of prudence in some assumptions while others are closer to a ‘best estimate’ approach. Some assumptions may also be more uncertain or have a greater effect on the measurement of liabilities than others. As such, trustees should pay closer attention to the prudence included in these assumptions and ensure the level of prudence in individual assumptions is sufficient for them to be confident it would not undermine their aims for low dependency.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with our approach for not expecting a stochastic analysis for each assumption to demonstrate that further employer contributions would not be expected to be required for accrued rights, but rather focussing on them being chosen prudently? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

Discount rate

We recognise that for the code, setting a discount rate limit limits schemes’ flexibility. There are a number of scenarios where we believe greater flexibility in the discount rate for the low dependency funding basis would be justified and compliant with the legislative principles.

For example, trustees taking a more dynamic approach to discount rates would be at odds with an approach where a more long-term fixed rate was set out in our code.

We also recognise that it would be burdensome and inefficient for TPR to have to frequently update the discount rate in our code to account for market conditions or to set rules for the examples above. We do not see that this is a useful or effective approach for the code.

We believe a better approach for the code is to focus on controlling the level of risk assumed in the investment strategy and then set principles for setting the actuarial assumptions consistent with that assumed investment strategy. This approach also fits with the legislative principles of a low dependent investment strategy with actuarial assumptions consistent with that strategy.

We have set out in the code that we expect most schemes will use either (or a combination of) the following approaches:

- The use of a risk-free rate plus an addition based on the prudent expected net longer-term return of the low dependency investment allocation.

- The use of the yield, adjusted prudently for expected defaults and expenses etc on cash flow matching assets which they already hold ('dynamic discount rate').

For these purposes, the risk-free rate referred to above could be gilts or an alternative, for example, a swaps rate.

For the dynamic discount rate approach, trustees should only take additional credit in the low dependency funding basis for the assets they hold. We also believe it is appropriate to set out some boundaries that are consistent with the principle of low dependency.

In particular:

- the assets used to determine the discount rate should be appropriate matching assets that satisfy the principles we have set out in the broadly matched section

- there should be an appropriately prudent deduction for default and downgrade risk as well as expenses

Where schemes have not yet transacted with such a credit asset, we do not think it is prudent to assume they will be able to purchase such assets in the future with yields higher than could be justified by reference to long term yields. Trustees should, therefore, only take additional credit in the low dependency funding basis for the assets they hold.

Consultation questions:

- Do you agree that the two approaches we have set out for the discount rate for the low dependency discount rate (LDFB) are the main ones most schemes will adopt? Should we expand or amend these descriptions, if so, how?

- Should we provide guidance for any other methodologies?

Other assumptions

We don’t believe it is appropriate at the current time for TPR to prescribe all the other assumptions within the code. However, we do think it is appropriate to provide guidance on setting the assumptions to the trustees, particularly the financial assumptions. Otherwise, this leaves the potential for a combination of a lack of prudence in each assumption, which one by one may not be material, but which could add up to an overall material impact and undermine the principle of low dependence.

We have, therefore, decided on an approach that aims to balance these competing elements by providing principles and guidance in the code.

Expenses

In our first consultation, we said that we consider a reserve for future expenses should be included to be consistent with the principle of low dependency unless the trust deed and rules explicitly require the employer to cover the full costs. We continue to believe this is the case, and responses generally supported this approach.

Therefore, our approach for the low dependency funding basis is that a reserve for future expenses expected to be incurred on and after the relevant date should be included for schemes where the trust deed and rules does not explicitly require the employer to cover the full costs. Even for schemes where the trust deed and rules does require the employer to cover the full cost, consideration should be given to allowing for a reserve.

However, there is significant complexity in TPR defining such an assumption. Expenses will vary between schemes and depend on several different factors – not least scheme size. We will provide some guidance in the code to help ensure that schemes take a consistent approach, but we do not think it would be appropriate to define the assumption at this stage. Trustees will be better placed to make an appropriate assumption based on their individual position. We will, however, require the assumptions used to be reported to us.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with the guidance and principles set out in Appendix 3 and 4? Are there any specific assumptions here you would prefer a different approach? If so, which ones, why and how would you prefer we approached it?

Code chapter 5 – Relevant date and significant maturity

Definition

We set out in our first consultation different ways in which maturity can be defined relating to the requirement for schemes to reach low dependency by the time they are significantly mature. The nature of the risk in relation to maturity focusses on the proportion of assets being paid out as cash flows. We set out that in our view, duration was the most appropriate methodology to capture this risk while avoiding some of the disadvantages the other options presented. This was supported by an overwhelming number of respondents to our consultation. Respondents also supported using the Fast Track low dependency actuarial assumptions to calculate duration.

In their draft regulations, the DWP proposed including in the legislation duration as the measure of maturity while delegating down to TPR – through the Code – definition of the appropriate duration point. They are also proposing that a scheme’s low dependency actuarial assumptions are used as the basis to calculate this. Therefore, we have drafted the code to be consistent with this.

Setting the point of significant maturity

We set out in our first consultation our proposal that significant maturity should be the region of when the scheme has a duration of 12 to 14 years. There needs to be a balance between not setting this point too early – and so putting pressure on schemes to reach it too quickly – versus not setting it too late and a scheme running on with excessive investment risk when the scheme is already significantly mature.

We recognise that there is no ‘one answer’ to this question, and it is a balancing act. Respondents to our consultation agreed with the range we set out with a preference for the later point within that (ie duration 12).

We also considered using a range, and many people supported that approach as helping to add flexibility for schemes. The FIS regulations require the Regulator to specify a “date [the scheme] reaches the duration of liabilities in years”, rather than a range. In any event, we are not convinced that, in practice, a range will help schemes or provide them with additional flexibility. If we were to, for example, set the range in the code as duration 12 to 14 years, this would add little to an approach of setting it as a single point of 12 with schemes still free to set their own relevant date and at an earlier stage than significant maturity.

We have therefore used a single point and to set that at the later point in time we consulted on – namely duration 12.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree that a simplified approach to calculating duration for small schemes is appropriate?

Possible alternative approaches

Recent volatility in the bond market has illustrated one of the downsides we highlighted in our consultation around using duration. Namely, it is sensitive to the prevailing gilt yields, and the increase in those yields over 2022 has materially reduced the period to significant maturity.

For example, the differences in market conditions between 31 March 2021 and 31 October 2022 and using a low dependency discount rate of gilts + 0.5%, has resulted in the duration for a scheme of typical maturity falling by around four calendar years and the time until a scheme is expected to reach duration 12, by around 8 years.

As such, there has been significant reflection and discussion regarding the use of duration as a fixed metric for significant maturity. We are also aware that the DWP have received a number of responses to their consultation on the draft regulations questioning whether duration remains the appropriate measure or whether there are additional mechanisms that could be used.

Therefore, while the code reflects the draft regulations, we are aware that the DWP may be considering responses to its consultation and possible approaches to measuring maturity.

If the DWP decide to maintain duration as the maturity measure for all schemes, then there are alternative approaches which could be used to help reduce the volatility. We have set three possibilities below:

- Use a fixed set of low dependency assumptions, for example, based on 0% real gilt yields, to set duration meaning the assumptions used would not automatically move in line with market conditions. These assumptions could either be set in the regulations or delegated to us to prescribe, meaning we would have the scope to review and revise them from time to time. Using this approach would mean the period until the scheme reached significant maturity would be relatively stable as only scheme experience should affect it (unless the assumptions are revised).

- Use a smoothed approach over a period up to the date of the calculation. For example, the duration could be based on the average of the last day of the previous 36 months prior to the date of calculation. There are different ways this smoothing could work, including:

- taking an average of the discount rates and other financial assumptions

- taking an average of the calculated duration (using market-based low dependency assumptions)

- Set the point of significant maturity in the code at a lower duration than that we use for our Fast Track parameters. For example, the definition in the code could be 10 years, whereas for the Fast Track parameters we use 12 years. Our guidance and code could also then explain that we expect schemes to plan to set their relevant date for achieving low dependency at a time around duration 12 years. This is unless the covenant strength is such that the trustees are confident they can rely on the covenant to support the risk for the period between duration 12 years and 10 years. Under this approach, the legal definition of significant maturity would still move with market conditions. However, if a scheme aims for an earlier date, its relevant date should not normally need to change if it remains before 10 years.

The first two options would require a small change to the wording in the current draft of the regulations. The third approach could be achieved within the current draft regulations.

Consultation question:

- Do you think setting an earlier point for significant maturity within Fast Track as compared to the code (as described in option 3 in this section of the consultation document) would be helpful for managing the volatility risk of using duration? If yes, where would you set it and why?

The period after significant maturity

In our consultation, we set out that after significant maturity, we would expect a scheme to at least maintain an approach consistent with low dependency. They may wish, however, to set additional objectives, such as, moving towards a buy out aligned strategy or a strategy that is lower risk.

We recognise that there may be circumstances where a scheme wishes to assume a lower standard than set out in the low dependency funding basis at or after significant maturity but rely on other forms of security to support the additional risk – for example, assets held in escrow. This approach could be beneficial for schemes in some circumstances, including where the employer or guarantor would prefer to plan to fund the scheme to a lower level but provide additional support via a contingent asset.

In its consultation, the DWP asked whether more risk-taking could be permitted after significant maturity as long as this can be supported by high-quality contingent assets (including cash in an escrow account) provided by another company within the group or a third party. They also asked whether to impose a limit on risk-taking after significant maturity as a percentage of total liabilities.

In our view, it is important that any additional flexibility in the regulations is subject to defined parameters around the security in place that supports additional risk beyond low dependency. We believe it is important not to introduce any material additional risk above this as it would undermine that low dependency principle.

We believe that any assumed risk-taking beyond low dependency after significant maturity should be supported by high quality assets – including contingent assets. We are less convinced that allowance for future sponsor contributions would be appropriate mitigation for extra risk since that would undermine the low dependency principle. For example, if the employer does not have assets that it could put forward as security but has significant cash flows and affordability. In that case the assets could be put in escrow in the period before and after their relevant date, and the risk in the low dependency funding allocation increased appropriately in line with the value of that escrow.

Were such an approach to be accepted by the DWP, there are questions about how the transition from a scheme’s journey plan to their planned investment strategy at the relevant date should be managed. For example, additional risk in the low dependency investment allocation with security to support that should be factored into the journey plan, low dependency funding basis and therefore technical provisions. It would not be sensible, for example, for a scheme to be assuming a de-risking path towards a funding basis and investment strategy based on low dependency and then to assume re-risking in light of additional security justifying a lower funding target and investment strategy carrying more risk.

We have not here considered the differing options as the DWP is considering the responses to its consultation. We will discuss these issues and the responses to the DWP’s consultation with the DWP and the industry over the coming months.

Code chapter 6 - Assessing the strength of the employer covenant

The draft funding regulations set out the requirement under the funding and investment strategy for schemes to have a journey plan towards low dependency at significant maturity. As part of that, the funding and investment strategy requires that the scheme’s journey plan adheres to the supportable risk principles. Under these, trustees must ensure that the level of risk taken is:

- dependent on the strength of the employer covenant, where more risk can be taken if the covenant is strong

- subject to the above, dependent on the maturity of the scheme

In this section of the code, we have set out the key considerations and expectations for trustees relating to how they should assess their employer covenant strength.

Aligning the strength of the covenant with the risks the scheme is taking was a principle that underpinned much of our current DB funding code and is a key part of integrated risk management (IRM). As such, it is unlikely to be a new concept or approach for most pension schemes that will have processes and approaches in place to assess the strength of their employer covenant. However, it is the first time legislation has directly referenced this need. Therefore, we have set out our proposals for how trustees should approach their assessment of the employer covenant in light of the legislation in our draft code.

The concept of ’reasonable affordability‘ is also proposed to be introduced into legislation in relation to recovery plans. How we expect trustees to assess reasonable affordability will be specifically addressed in the Recovery plan chapter of the code.

The code introduces employer covenant support, broken down into:

- the employer’s financial ability to support the scheme, including:

- The employer’s cash flows

- The employer’s prospects

- contingent asset support

When assessing an employer’s ability to support the scheme, we introduce three periods trustees should consider:

- Visibility over employer’s forecasts typically covering the short term.

- Reliability where trustees have reasonable certainty of available cash to fund the scheme.

- Longevity of the covenant, which is the maximum period trustees can reasonably assume that the employer will remain in existence to support the scheme. This forms part of the trustees’ assessment of employers’ prospects and is important when determining an appropriate journey plan.

The code sets out how trustees should assess an employer’s free cash flow including relevant adjustments, to understand how cash can support funding and investment risk. Where the employer doesn’t prepare cash flow information, the code sets out alternative methods trustees could use.

The code sets out the other factors likely to affect the performance or development of the employer(s) business and how these factors might affect the reasonableness of the employer’s forecasts, profitability, free cash generation and balance sheet strength (including financing arrangements) beyond the visibility period. Together, these factors allow trustees to assess the employer’s prospects and will, in turn, inform the trustees’ view on covenant longevity.

The code sets out trustee considerations when valuing security arrangements and guarantees. It also discusses the concept of a ’look through guarantee’ – a guarantee that largely replicate the obligations placed on a statutory employer and allow the guarantor to be treated as an employer for the purpose of assessing covenant support.

We are updating our covenant guidance to supplement the principles and approaches set out in the code. We will provide more examples to help trustees in their assessment of all three covenant limbs. The guidance will also consolidate previous regulatory messages and guidance on areas including covenant monitoring, distressed employers, improving scheme security, fair treatment, asset-backed contribution arrangements, not-for-profit, non-associated multi-employer schemes. We plan to consult on this in the coming months.

Consultation questions:

- Do you agree with the definitions for visibility, reliability, and longevity? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the approach we have set out for assessing the sponsors cash flow? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the approach we have set out for assessing the sponsors prospects? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the principles we have set out for contingent assets, ie that i) it is legally enforceable and ii) it will be sufficient to provide that level of support? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the approach we have set out for valuing security arrangements? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the approach we have set out for valuing guarantees? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the approach we have set out for multi employer schemes? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the approach we have set out for not-for-profit covenant assessments? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

Code chapter 7 – Journey planning

Introduction

The second element of the funding and investment strategy is the trustees’ plan to bridge from the current funding position to the long-term funding target set in the funding and investment strategy (the 'journey plan').

In the code, we present two distinct periods we expect the trustees to consider when setting their journey plans.

- The period of covenant reliability. This is where the trustees can be reasonably confident about the approximate level of the employer’s available cash to fund the scheme into the future. Reliability is defined in the covenant section.

- The period after covenant reliability is where they have less certainty over the ability of the sponsor to provide the necessary support.

This section of the code discusses each and sets how we expect trustees to satisfy themselves that their journey plan is consistent with the supportability principles.

Maturity

Before discussing journey planning in more detail, we set out the role we think maturity plays in their consideration.

The supportability principles set out, that subject to the strength of the employer covenant, more risk can be taken when a scheme is further from the date of significant maturity.

Immature schemes have longer investment time horizons, the further they are from significant maturity.

These longer time horizons mean they are in a better position to ride out periods of market stress without a significant concern about cash flow management and needing to sell significant proportions of their assets during these periods to pay pensions due. This longer time horizon means they have longer to benefit from the potential for extra returns as well as additional support from their sponsor by way of contributions.

This increased risk therefore has the potential to improve the upside potential for scheme funding over the longer term.

However, taking greater levels of risk, even over a longer time horizon does not come without the potential for larger downside risks. This is due to a combination of both:

- investment risk is greater and so has larger downside risks when looking towards the tail of the distribution

- funding risk, if taking greater investment risk flows through to a higher discount rate, then all else being equal, there is less money in the scheme

In our view, it is reasonable for trustees of more immature schemes to assume higher levels of funding and investment risk over time. This is still subject to the strength of the employer covenant as set out in the regulations.

Applying this approach

We have made some allowance for this in relation to journey planning (and also in the Technical Provisions (TP) chapter).

In relation to the journey plan, we have set out a test for schemes to assess the maximum risk they should assume in the journey plan. We expect schemes to plan to de-risk after the period by which they can rely on their employer being able to stand behind that maximum risk. This is covered in the journey plan section of our code and is described in the Journey plan – period of covenant reliability section of this consultation document.

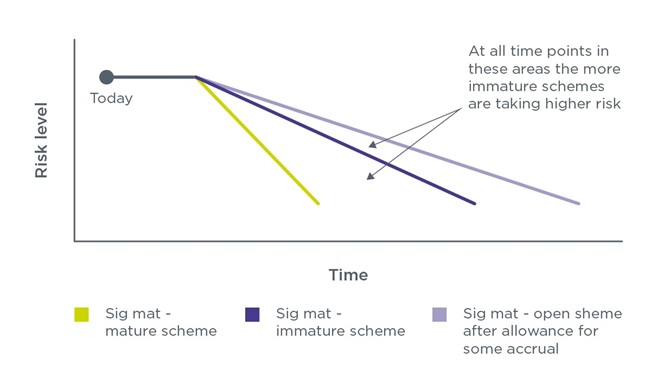

For more immature schemes, this de-risking path will have a much more gradual slope and shallower gradient than a more mature scheme, reflecting the longer time to significant maturity. This means that, if two schemes are equal in every other way, the more immature scheme will be able to allow for taking higher levels of risk over a longer period.

This extra risk taking can result in higher discount rates and so lower the TPs and lead to a lower level of funding required.

For open schemes, we have also set out in the journey plan and TP section that we think it reasonable for them to make some allowance for future accrual. In Fast Track, we are setting this to six years, however, in Bespoke, schemes will be able to provide justification for a longer period, if they have the confidence and can provide evidence that this is the case.

This will, in effect, allow open schemes to assume they will mature on a slower path and that increased immaturity can be reflected in their journey plans and TPs.

In all cases, if the period of reliability of the employer extends or is reviewed – say at a subsequent valuation – and deemed to be able to be extended, then the point at which schemes should assume de-risking begins can be extended.

This is illustrated in the graphic below.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with how we approached how maturity has been factored into the code? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative in particular with reference to the draft regulations?

Journey plan - period of covenant reliability

While schemes’ journey plans may stretch over many years, it is still important that schemes focus on the short to medium-term aspects as well. They should have plans in place to manage their funding position if a deficit emerges or increases and a recovery plan is required. Managing short to medium-term risk helps ensure that the scheme is on the right track for its longer-term goals and can ‘get back on track’ for its journey plan if, for example, markets perform worse than expected.

Therefore, it is important that trustees consider these risks in their funding and investment strategy and understand the impact they might have on their scheme’s funding level and what actions they might need to take if those risks emerged.

There are many different tools and approaches that trustees can use to do this – from simple deterministic scenario analysis to VAR models to full stochastic modelling. We do not intend on setting out detailed and prescriptive expectations regarding what methods trustees should use, since scheme circumstances will vary. We are setting out some minimum level expectations but we expect many schemes will need to go beyond these while being proportionate to their circumstances.

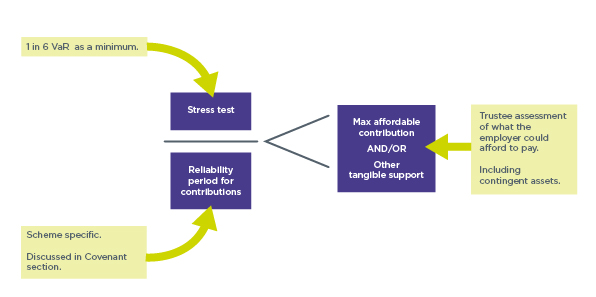

We believe a key approach that trustees should take is to consider a downside event and compare this to the ability of the employer to repair any deficit that would emerge from such an event over the period of covenant reliability where they are confident the sponsor can afford to make payments to the scheme.

While the legislation provides the principle that the level of risk should be dependent on the strength of the employer, it does not provide for a definition of the level of dependency that is appropriate. We are aware that many schemes look at downside events in the region of 1 in 20 as part of their risk assessment processes. This can be very useful for schemes to consider and the sorts of actions they may take.

However, as a minimum, we have chosen 1 in 6 over one-year downside event as reasonable in this context. Such an event could be expected to happen over the next two valuation cycles for a scheme so is well within what is plausible. It is also consistent with the approach we are taking to the stress test in Fast Track which will make it simpler for trustees while being consistent with other aspects of the framework.

We have stated that we expect trustees to:

- consider the affordability of the employer

- consider the period over which they have reliability of that affordability (as defined in the covenant section)

- compare this to the stress test outcomes

Trustees should keep the risk levels in this part of their journey plan within these parameters during the period of covenant reliability.

Trustees can also use this approach to determine the maximum risk that the scheme should be assuming during this period ('the maximum risk test'). This is the largest deficit increase the sponsor could afford to remedy in line with the above approach. In practice, trustees may prefer to assume a lower level of risk to better protect themselves against more extreme adverse market movements.

The following graphic is included in the code to illustrate this approach:

Consultation questions:

- Do you agree with the way in which we have split the journey plan between the period of covenant reliability and after the period of covenant reliability? If not, what would you suggest as an alternative?

For the period of covenant reliability

- Do you agree that trustees should, as a minimum, look at a one-year 1-in-6 stress test and assess this against the sponsors ability to support that risk?

- Do you agree that if trustees are relying on the employer to make future payments to the scheme to mitigate these risks, then the trustees should assess the employer’s available cash after deducting DRCs to the scheme and other DB schemes the employer sponsors?

- Do you agree that this approach is reasonable for assessing the maximum risk that trustees should take during the period of covenant reliability?

Journey plan - period after covenant reliability

This section of the code discusses the period of the journey plan after covenant reliability where trustees will have less confidence in the level of support the sponsor will be able to provide after the reliability period.

Although trustees will be less confident in the strength of employer covenant after the reliability period, they should be assessing the employer longevity and prospects. It is then reasonable for them to factor that strength into their journey plan.

This will drive the level of risk, it is then appropriate for them to assume, including the nature and shape of trustees’ journey plan towards low dependency. We set out in the code the main approaches to shapes of journey plan and several considerations that we expect trustees to take in setting it. We are not prescribing the approach we expect trustees to take since that will depend on their specific circumstances and their assessment of their covenant.

However, we set out that where the maximum level of risk is being assumed in the period of covenant reliability (maximum risk test), we believe in the period after the end of covenant reliability and before relevant date, we would expect the trustees to plan to de-risk their investment strategy. In these circumstances, we would expect the trustees to choose a de-risking strategy with no more risk than a linear de-risking strategy starting at the end point of covenant reliability.

If the trustees are aware of reasons why the covenant might deteriorate more quickly, we would expect that to be reflected in the strategy they choose. This will be particularly relevant for schemes where the relevant date is after the period of covenant longevity.

If the scheme is assuming less than the maximum level of risk the sponsor can support, it may be reasonable for them to factor holding that level of risk for a period of time after the sponsors reliability, as the trustees will have some level of ‘buffer’ for the sponsors affordability to decrease, but still be within the maximum risk test. This is dependent on the trustees’ assessment of the prospects and longevity of the covenant.

For open schemes, we believe it can be appropriate to assume a reasonable allowance for future accrual and new entrants which will delay the time the scheme is assumed to reach significant maturity. What is a reasonable allowance in this context is discussed further in the section on Technical Provisions (TPs).

The trustees will need to consider how the investment strategy is reflected in the setting of the assumptions for TPs and the funding risk in the journey plan. This is also discussed further in the section on TPs.

We would expect the trustees to consider what level of risk is right for them and understand the level of risk in their funding and investment strategy. This will depend on the level of risk assumed in the investment strategy and to what extent this is reflected in the TPs. The choice of relevant date will also be a factor in determining how much risk is appropriate.

In their planning we would expect the trustees to ensure that any future strategy will be practicable. For example we would expect the trustees to consider:

- their investment governance model and whether it can support the planned de-risking strategy, for example the frequency of reviews and changes to asset allocations incorporated in their plan.

- the timeframes for significant de-risking. We would not expect the Trustees to assume significant de-risking to occur instantaneously or over a short time period where in practice they would expect this to take longer to minimise risk. This is especially true of any de-risking which is assumed to occur at or near significant maturity.

- the duration based measure for significant maturity. We would expect the journey plan to reflect this measure in a proportionate way. Therefore we expect that de-risking in the journey plan should be measured, to some extent, against duration.

Consultation questions:

For the period after covenant reliability

- Do you agree with the considerations we have set out regarding de-risking after the period of covenant reliability?

- Do you agree with our approach of not being prescriptive regarding the journey plan shape?

- Do you agree with our approach that the maximum risk trustees should assume in their journey plan is a linear de-risking approach where they are taking the maximum risk for the period of covenant reliability?

Code chapter 8 - Statement of strategy

Introduction

This section of the code summarises the need for a statement of strategy and its main contents.

Once a scheme has determined or revised its funding and investments strategy, trustees must prepare a statement that is made up of two parts:

- Part 1, which records the funding and investment strategy.

- Part 2, which records various supplementary matters, including various details in relation to the journey plan, how well the funding and investment strategy is being implemented, the main risks to the strategy and how they are being managed.

The statement of strategy will be a written statement that illustrates the main risks faced by the scheme in implementing the funding and investment, detailing how the trustees or managers intend to mitigate or manage them, along with other details about the scheme which are covered in our draft code. The statement of strategy must be submitted to the TPR at the same time that they submit an actuarial valuation.

The purpose of the statement of strategy is to act as a tool for trustees to facilitate engagement with both the employer and us, while increasing trustees’ accountability. The statement of strategy, alongside the funding and investment strategy, will encourage a greater focus on long-term planning and risk management and allow us to assess the approach, methods and assumptions underpinning the trustees’ strategy.

All schemes will be required to submit a statement of strategy. The legislation sets out some minimum requirements for what trustees of all schemes need to include in their statement of strategy. Further details of what this entails are set out in the code.

Format of the Statement of strategy

Regulation 18 of the draft regulations requires the statement of strategy to be submitted in a form as set out by the regulator. We are not yet consulting on the form of the statement of strategy to be submitted to us. Therefore, during the code’s consultation period, we will be engaging with industry to discuss how the information in the statement of strategy fits with the other documents and information that trustees are already required to produce. The other documents include the statement of funding principles, statement of investment principles, recovery plan and schedule of contributions along with the new effective system of governance and own risk assessment requirements.

We intend to ask for schemes to provide information electronically, including information taken from other scheme documents as well as the statement of strategy. We want to explore how best to obtain information from schemes in a way that minimises any additional burden and administrative costs.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with our explanation of the statement of strategy and are there areas it would be helpful for us to expand on in this section?

Applying this in practice

In this part of the code, we are setting out our expectations in relating to how trustees should approach their valuations and recovery plans and how the elements in part 2 should be integrated into their funding solutions.

Many of our expectations across these areas are linked and overlap. Where there is an overlap, we have not repeated our expectations but referenced the relevant chapters or sections in other parts of this code.

This part of the code covers:

- technical provisions

- recovery plans

- investment and risk management considerations

Code chapter 9 — Technical provisions

Main requirements

Our draft code sets out the key requirements in relation to the process and calculation of a scheme’s technical provisions (TPs). The legislation requires that the TPs are calculated at each valuation and represent the amount required, on an actuarial calculation, to make provision for the scheme’s liabilities.

These must be calculated in a way that is consistent with the scheme's funding and investment strategy, as set out in the scheme's statement of strategy.

The economic and actuarial assumptions used in the calculation of the TPs must be chosen prudently, allowing a margin for adverse experience. The mortality assumptions and demographic assumptions must be chosen using prudent principles.

Consistency with the funding and investment strategy

The new requirements for the funding and investment strategy require that trustees set out a journey plan for their investments for the period before significant maturity and set out a low dependency investment allocation from that point. For the journey plan, the level of risk taken is dependent on the strength of the employer covenant. This is covered in the previous sections.

The TPs must be consistent with the funding and investment strategy. To be consistent, we believe the TPs must meet the following conditions:

- For the period after the relevant date, the assumptions used in the TPs must be the same as or stronger than those in the low dependency funding basis.

- For the period before the relevant date, the TPs must also be consistent with the scheme’s journey plan. We would expect the trustees to understand how the assumptions for TPs at future valuations are expected to change as the scheme progresses through the journey plan

Setting the assumptions for TPs

The individual assumptions used should be chosen consistently with the overall level of prudence targeted of the TPs.

We expect the trustees to understand the risks in their funding strategy. This includes how robust the strategy is to changes in market conditions in future. Our general expectation is that yield curves should be used for economic assumptions. This applies particularly before the relevant date, where the journey plan expects gradual de-risking over time, and this is reflected in the discount rates. However, we would expect any approach to be proportionate to the circumstances of the scheme.

In relation to consistency with the funding and investment strategy, for the period after the relevant date the discount rate must be set assuming the scheme is invested in the low dependency investment allocation. Before the relevant date, the discount rate should not assume investment returns greater than would be justified allowing for the current and future investment strategy in the journey plan.

In the section on the low dependency funding basis, we set out our expectation that the inflation assumptions should be derived unadjusted from the market expectation for inflation. In the calculation of the TPs we think an adjustment such as an ‘inflation risk premium’ may be appropriate. The level of such an adjustment should be prudent and depend on the investment strategy and the extent to which the liabilities are matched against movements in inflation.

Consultation question:

- Do you agree with how we have described the consistency of the TPs with the funding and investment strategy? If not, why not and what would you suggest as an alternative?

Open schemes

As part of our first consultation, we consulted on the principle that open schemes should have the same level of security as closed schemes. Most respondents agreed with this principle, but there were concerns over whether this would be overly restrictive in relation to investment allocations on the basis that open schemes should be able to invest in more illiquid assets and over a longer time horizon.

We also consulted on the principle that future accruals should not compromise the security of benefits already accrued. Again, most respondents agreed with this, but those that raised concerns highlighted the potential for it to be overly restrictive.

Although it is uncertain that any open scheme will remain open and for what time period or what level of new entrants will flow to the scheme, we do think it could be appropriate to make a reasonable assumption for future accrual and/or new entrants in determining the TPs before the relevant date. However, where such an approach is used, trustees should ensure it does not materially undermine the principle of the same level of security for open and closed schemes.

This would mean that an open scheme taking into account some future accrual will be assumed to take longer to reach significant maturity than an equivalent closed scheme. Therefore, it can be assumed that risk will be taken for longer and this will feed through into the journey plan and so, the assumptions for the TPs.

However, it is important that the principle that the past service in open schemes should have the same level of security as closed schemes is not undermined. Therefore, that future accrual assumption should not normally extend beyond the period where the scheme has a high level of confidence that the scheme will be open and the employer covenant will remain in a position to support accrual. For Fast Track purposes we are setting this as six years, which is in line with our view of a reasonable assumption for covenant reliability. For code compliance, schemes can make a scheme-specific assumption, as long as it is justified by the covenant reliability, and, like other demographic assumptions, it should be evidence-based and prudent.

Consultation questions:

- Do you agree that open schemes could make an allowance for future accrual – thereby funding at a lower level - without undermining the principle that security should be consistent with that of a closed scheme?

- Do you agree that this should normally be restricted to the period of covenant reliability? If not, why not and what you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with our principled based approach to future service costs? If not, why not and what you suggest as an alternative?

Code chapter 10 - Recovery plans

Legislation already set out matters that the trustees must take into account when setting their recovery plan. The draft DWP regulations introduce an additional principle to require the trustees or managers, when determining whether a recovery plan is appropriate, to follow the principle that funding deficits should be recovered as soon as the sponsoring employer can reasonably afford to.

In this section of the code, we are setting out or expectations for how trustees should approach this new principle.

Reasonable affordability

Reasonable affordability of the sponsor has been a feature of TPR’s guidance to trustees when determining contributions for recovery plans for several years. Our existing DB code highlights affordability as a key factor to consider.

Our draft code sets out three key steps we expect trustees to go through in determining what is reasonably affordable.

- Assess the employer’s available cash (comprising of an employer’s free cash flow and liquid assets).

- Assess the reliability of that available cash over the short, medium and long term.

- Determine whether any of the available cash could reasonably be used by the employer other than to make contributions to the scheme (‘reasonable alternative uses”). Our code expands on these concepts to give guidance to trustees. The last of these – the reasonable alternative uses – is probably the one that requires the most discussion with sponsors and judgement on behalf of trustees.

We are aware of concerns that the principle of deficits being paid off as quickly as reasonably affordable could lead to trustees pushing for much higher levels of deficit repair contributions (DRC)s and much shorter recovery plans, prioritising pension schemes over other uses including how a business needs to invest in order to grow.

Our view is that the principle of 'reasonable affordability' allows room for trustees and employers to agree recovery plans that take full account of the sponsor’s needs to invest in its business and use its available resources for appropriate means. To try and make this clearer, we introduced the concept of ’reasonable alternative uses' into our draft code and set out how we would expect trustees to assess this in the context of what is reasonably affordable for the sponsor to pay to the scheme.

We have highlighted three main alternative uses of employer resources:

- Investment for sustainable growth.

- Covenant leakage where value moves out of the employer and is not recoverable or expected to be repaid on demand.

- Discretionary payments to other creditors.

It is not the case in our view that the scheme should be prioritised over all these alternative uses in all circumstances. Investing for sustainable growth is a key and necessary part of growing or maintaining a business. Distributions to shareholders and other creditors may form part of normal business operations. However, there are different circumstances when we believe these alternative uses are reasonable and when the scheme should have a higher priority. They are set out as principles in the draft code.

We expect trustees to consider several factors when assessing whether the alternative uses are reasonable, including:

- the maturity of the scheme

- the scheme’s funding level

- the level of prudence in the TPs

- the reliability of the level of available cash in the future

- the fairness of treatment between the scheme, other creditors and shareholders

We have not set out any benchmarks for recovery plan length in the Code. We do not believe that the legislative principles and the need for scheme and employer-specific circumstances to be taken into account lead themselves to a one-size fits all benchmark for recovery plan length. However, in Fast Track, we have set a limit of six years and for recovery plans longer than that we will expect the trustees to justify their approach based on the principles in our code.

Consultation questions:

- Do agree with our approach to defining Reasonable Alternative Uses? If not, why not and what you suggest as an alternative?

- Do you agree with the description in the draft Code of the interaction between the principle that funding deficits must be recovered as soon as the employer can reasonably afford and the matters that must be taken into account in regulation 8(2) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Funding) Regulations 2005?

- Do you agree that reliability of employer’s available cash should be factored in when determining a scheme’s recovery plan length?

- Do you agree with the principles we set out when considering alternative uses of cash? If not, which ones do you not agree with and why? What other principles or examples would it be helpful for us to include?

Post-valuation experience

We believe post-valuation experience can be a helpful tool for trustees to allow for market volatility when finalising their scheme valuations and setting recovery plans. The 15-month window from the statutory valuation date to when trustees must agree the recovery plan gives trustees an opportunity to assess any changes since the valuation date. This was particularly useful, for example, for schemes with valuation dates in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic hit financial markets and businesses.

However, if post-valuation experience is being allowed for, we expect schemes to follow the principles that:

- both the positive and negative aspects are included

- the impacts on assets and liabilities are included