This policy provides guidance on our approach to the investigation and prosecution of the new criminal offences of ‘avoidance of employer debt’ or ‘conduct risking accrued scheme benefits’, which appear in sections 58A and 58B of the Pensions Act 2004, and Articles 54A and 54B of the Pensions (Northern Ireland) Order 2005. It provides a comparison of these new offences with other related powers, and includes some examples of the types of behaviour that may fall within, and outside, the scope of these new offences.

This policy does not provide guidance on our approach to any of our other powers, including our contribution notice (CN) power and our powers to issue a financial penalty for avoidance of employer debt or conduct risking accrued scheme benefits.

Published: 29 September 2021

Who is this policy for

This policy is for anyone seeking to understand our approach to investigating and prosecuting these criminal offences.

It sets out how we interpret these powers, with examples of how we will put them into practice. This policy should be read in conjunction with our Prosecution Policy, which covers our general approach to criminal investigations and prosecutions for all offences.

Terminology

For ease of reading, when we refer to 'someone' in this guidance, it includes any legal person, for example a company as well as an individual. When we refer to an ‘act’, it also includes a failure to act, a series of acts, and/or a course of conduct.

For simplicity, we will refer to the offences as being under sections 58A and 58B of the Pensions Act 2004, but those references should be interpreted as being to Articles 54A and 54B (as applicable) of the Pensions (Northern Ireland) Order 2005 where the jurisdiction is Northern Ireland.

All references in this policy to what we will and will not do, and all references to prosecution, are confined to our approach to prosecution of either or both of the offences under sections 58A and 58B of the Pensions Act 2004.

A: Introduction

The offences in sections 58A and 58B are potentially very broad in scope, due to the wording of the ‘act elements’ (described below). However, the vast majority of people do not need to be concerned - we don’t intend to prosecute behaviour which we consider to be ordinary commercial activity. We will investigate and prosecute the most serious examples of intentional or reckless conduct that were already within the scope of our CN power, or would be in scope if the person was connected with the scheme employer.

If we come across the kind of behaviour that would engage these new offences, we will consider whether we will prosecute and/or whether another power should be pursued (for example, a section 38 CN or a financial penalty). Our approach to situations where we have more than one power available to us is set out in our Overlapping Powers policy.

We operate in a risk-based and proportionate way when considering the use of our powers, and the operation of the new offences will follow this existing approach. We use our powers where it is appropriate and reasonable to do so, in pursuit of our statutory objectives. This policy will be reviewed and may be revised following any court decisions in relation to the offences and to reflect our experience.

Please note that the prosecuting authorities for these offences vary within the United Kingdom.

- In England and Wales, prosecution of these new offences may be brought by us or the Secretary of State, or by (or with the consent of) the Director of Public Prosecutions.

- In Northern Ireland, prosecution may be brought by us, or the Department for Communities (Northern Ireland), or by (or with the consent of) the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland.

- In Scotland, public prosecutions are brought by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service.

Where any of the other bodies listed above are considering or asked to consider taking action in respect of the offences, we would expect to be informed and consulted.

This policy has been created by us alone and may not reflect the interpretation of these other bodies, or their approach to investigation or prosecution of these offences.

B: What this policy covers

In this policy, we:

- Describe the new offences, and the elements that make up each offence, who they can apply to, and our approach to ‘reasonable excuse’

- set out the relevance of clearance statements to these offences, and

- identify other TPR publications that may be of interest to readers.

The appendices to this policy:

- compare the offences to CNs and to the financial penalties in sections 58C and 58D

- describe our approach to some common behaviours and activities, and

- contain a case study where the contents of this policy are applied to a fictional set of facts.

C: The new offences

The offences can only be committed in respect of an occupational pension scheme that is not a money purchase scheme. In brief, the offences apply where:

- someone does or fails to do something which meets the relevant ‘act element’

- the person had the relevant ‘mental element’, and

- they didn’t have a reasonable excuse for acting in the way that they did.

These concepts are explained further below.

The new criminal offences do not have retrospective effect, which means that we can only prosecute people for acts that took place on or after 1 October 2021. However, we may take into account facts from before that date as part of our investigations, and those we’re investigating may wish to rely on those facts in their defence. This would be relevant, for example, where those facts indicate someone’s intention for the act which took place on or after 1 October 2021.

The ‘act elements’

The offences under section 58A and section 58B have different ‘act elements’.

Under section 58A, the ‘act element’ is met if a person does an act that:

- Prevents the scheme from recovering all or any part of the debt that is due from the employer under section 75 of the Pensions Act 1995

- Prevents that debt becoming due

- Compromises or otherwise settles that debt, or

- Reduces the amount of that debt which would otherwise become due.

The debt under section 75 of the Pensions Act 1995 is a statutory debt owed by the employer to the trustees of the scheme, which becomes payable in circumstances defined by the legislation. These circumstances include when the employer suffers an insolvency event, or the scheme is wound up. Section 75 requires the scheme actuary to estimate the amount needed to secure the scheme's liabilities with annuities bought from a regulated insurance company.

Under section 58B, the ‘act element’ is met if a person does an act or engages in a course of conduct that detrimentally affects in a material way the likelihood of accrued scheme benefits being received (whether or not the benefits are to be received under the scheme).

‘Accrued scheme benefits’ are benefits that have accrued before the act, or before the last act in the series. Benefits that members receive from the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) or under the Financial Assistance Scheme are to be disregarded when considering whether the act had a materially detrimental effect.

In deciding whether the ‘act element’ is met for the purposes of the offence under section 58B, we will take the same approach as when considering issuing a material detriment CN under section 38.

In particular, we will take account of the matters set out in section 38A(4) of the Pensions Act 2004, Code of Practice 12 (Circumstances in relation to the material detriment test, the employer insolvency test and the employer resources test) and the accompanying guidance and, where relevant, have due regard to past determinations, both by the Determinations Panel and any court.

The ‘mental elements’

The offences under sections 58A and 58B have different ‘mental elements’.

Under section 58A, the ‘mental element’ is met if the person intended their act to have the relevant effect.

By contrast, the offence under section 58B is committed where someone knew or ought to have known that their act would have a materially detrimental effect. In considering what the person ought to have known, we will look at the circumstances as they were at the time of the act, and not with the benefit of hindsight.

Reasonable excuse

Even if the relevant ‘act element’ and the ‘mental element’ are proven, a person will only commit an offence if they didn’t have a reasonable excuse for doing the act.

The legal burden is on the prosecution to prove the absence of a reasonable excuse (as is the case for the ‘act element’ and the ‘mental element’). However, this does not mean that the prosecution must identify and disprove every possible excuse open to someone. We expect those we investigate to explain their actions and put forward sufficient evidence of any matters that might amount to a reasonable excuse, and we will give them the opportunity to do so. We expect the basis for the reasonable excuse to be clear from contemporaneous records, such as minutes of meetings, correspondence and written advice.

Part (E) of this policy sets out the principles which we will apply when considering whether a person has a reasonable excuse for either offence. Appendix 2 sets out how we generally expect those principles to apply in a number of common situations.

D: Who is in scope

The offences can be committed by any person (regardless of their connection or otherwise with the scheme or its sponsoring employer), other than someone appointed as and acting within their functions as an insolvency practitioner.

In addition to applying to those who directly perform an act or carry out a course of conduct, the offences can also apply to a person who helps or encourages someone else to commit either of the offences. The person who helps or encourages (the ‘secondary offender’) is liable to be tried and punished in the same way as the person carrying out the act or course of conduct (who is known as the ‘principal offender’).

To establish ‘secondary liability’ under these offences, we would need to show that the secondary offender did not have a reasonable excuse for helping or encouraging the principal offender to do that act (rather than a reasonable excuse for the underlying act). Therefore, an adviser, whose advice assisted or encouraged an act that had the effect described in either offence, will not be liable if they have a reasonable excuse for advising in the way that they did. This would be the case even in circumstances where the principal offender did not have a reasonable excuse for their own act or course of conduct.

E: Our approach to reasonable excuse

What amounts to a reasonable excuse in any particular case will be fact- and circumstance- specific. If we decide to prosecute, the determination of whether a person has a reasonable excuse is ultimately a matter for the criminal courts (as is the case for the ‘act element’ and the ‘mental element’).

However, we would need to form our own view on whether the person had an objectively reasonable excuse for acting as they did as part of our investigation. The rest of this section describes the principles-based approach to how we will assess reasonable excuse.

When considering whether a person had a reasonable excuse, we will:

- Consider each person’s reasons for acting in the way that they did, and the reasonableness of those reasons. We will consider them in isolation of the actions of other parties and the reasonableness of those actions (unless the parties are acting together).

- For example, where a sponsoring employer is extending its borrowing, whether the lender had a reasonable excuse is not affected by the reasonableness of the actions of the employer or its directors.

- Take account of the circumstances in which the act took place.

- For example, we would be mindful of any time constraints which a person was subject to.

- Take account of the person’s own circumstances, including their duties, skills and experience and other relevant attributes.

- For example, if a director of the sponsoring employer has extensive experience of refinancing, this may be relevant to their awareness of potential options and viable alternatives (as discussed below).

There are three factors that will generally be significant in our assessment of whether a person has a reasonable excuse for either offence:

- The extent to which the detriment to the scheme was an incidental consequence of the act or omission.

- The adequacy of any mitigation provided to offset the detrimental impact.

- Where no, or inadequate, mitigation was provided, whether there was a viable alternative which would have avoided or reduced the detrimental impact.

These factors, which are explained in more detail below, will be given the weight we consider appropriate in each case. They do not lower the legislative tests for use of the criminal powers, but rather provide a framework to our approach to help people understand how we will approach their situation.

In addition to considering the three factors set out above (where relevant), we will assess all other relevant factors when reaching a view on whether a person has a reasonable excuse. These other factors may include:

- The extent of communication and consultation with the trustees of the scheme before the act took place.

- In the case of a person who owes fiduciary duties to the scheme, whether they complied with those duties when doing the act or carrying out the course of conduct.

- Where the person was acting in a professional capacity, whether they acted in accordance with the applicable professional duties, conduct obligations and ethical standards.

1. The extent to which the detriment to the scheme was an incidental consequence of the act or omission

The more incidental the detriment was to the person’s objective, the more that objective would tend towards establishing a reasonable excuse. The fact that a person’s act has the consequence of causing detriment to the scheme does not necessarily mean that the person does not have a reasonable excuse, whether or not they were aware of that consequence.

The centrality of the detriment to the person’s purpose will be fact-dependent. The greater the person’s proximity to the scheme, the more likely it is that we would view this consequential detriment to the scheme as central.

Examples of scenarios in which the detrimental impact might be considered incidental would be where:

- The employer’s business is harmed by ordinary business activity conducted on arm’s-length terms by an unrelated party. This could be a supplier or customer terminating a business relationship, or a lender revising or terminating a lending arrangement, where their objective was unrelated to the scheme.

- The employer’s business is affected by protests organised by a pressure group opposed to the employer’s activities. The purpose of the pressure group is to protest the issue and disrupt the employer’s activities because of their opposition to those activities. The detriment to the scheme was an incidental consequence.

- The employer’s business is disrupted by industrial action organised by a trade union representing the interests of employees. The purpose of the trade union’s actions is to promote the interests of its members – the detriment to the scheme was incidental.

- A bank chooses not to lend to a sponsoring employer because of the risk that the pension scheme could cause the employer to become insolvent, which might expose the bank to losses. The employer subsequently fails due to its inability to refinance. The detriment to the scheme was an incidental consequence of the bank’s actions.

- A parent company, a research and development (R&D) business, has two subsidiaries, one of which sponsors a DB pension scheme. The parent company considers two proposals for investment but can only afford to fund one of them. Proposal 1 would be expected to grow the covenant of the employer and so benefit its scheme, whereas Proposal 2 would grow a sister company which is outside of the employer covenant. The parent chooses to invest in Proposal 2 because it is expected to generate more profit in the sister company than Proposal 1 would be expected to generate in the employer. The detriment to the scheme is incidental, despite the parent company’s proximity to the scheme.

Examples of scenarios in which the detrimental impact might be considered central, rather than incidental, would be where:

- A key supplier terminates a supply contract with the employer with the purpose of bringing about its insolvency, so the supplier can buy the whole of the employer’s business out of insolvency apart from the scheme. The detriment to the scheme was central to the supplier’s objective.

- A sponsoring employer can only afford to pay minimal dividends due to the funding requirements of its scheme. Its parent instructs the employer to direct new business to a new group company, which is not a sponsor in relation to the scheme, rather than conduct it through the employer. The employer becomes unable to properly fund the scheme as a result. The detriment to the scheme was central to the parent’s objective.

2. The adequacy and timeliness of any mitigation provided to offset the detrimental impact

The more the detrimental impact has been mitigated, the more likely the person is to have a reasonable excuse. Mitigation provided at an early stage is more likely to provide a reasonable excuse than mitigation after a lengthy period.

When considering the adequacy of mitigation, we expect the scheme to be treated fairly in relation to the other stakeholders in the employer, taking account of their relative financial interests, including their entitlements to value in the case of an ongoing employer and on the employer’s insolvency. This is similar to the way we assess mitigation in clearance cases.

The true impact of an act may not become apparent until some time after it occurs. We will take into account the circumstances which were known at the time of the act, or which would have been apparent had the person made reasonable enquiries at that time. If mitigation is provided after the act takes place, we will take account of what would be reasonable for the person to know, having made reasonable enquiries, at the time the mitigation was provided. We will generally expect mitigation to have been provided at or soon after the time of the act.

Examples of scenarios where the mitigation might be considered adequate would be where:

- An employer that is legally supported by the covenant of a wider group of companies is sold to a buyer, terminating the wider support arrangements. A combination of part of the sale proceeds being paid to the scheme and the provision of guarantees from suitably strong entities in the new employer group fully compensate for the loss of the seller group support.

- The employer grants security for the benefit of entities outside the direct covenant, but the security provided is subordinated to all present and future liabilities of the scheme.

- The employer makes cash transfers to a treasury company within its wider group as part of a routine cash sweep arrangement, but the employer is given an enforceable right to demand repayment at any time, and the treasury company is suitably strong enough to meet any such demands.

We recognise that it may not be possible for full mitigation to be provided in every situation where the ‘act element’ of section 58A or 58B is satisfied. We are likely to consider the factor described below as significant where full mitigation is not provided.

3. Where no, or inadequate, mitigation was provided, whether there was a viable alternative which would have avoided or reduced the detrimental impact

If a person could have undertaken a viable alternative course of action which would have had a less detrimental impact, that would suggest an absence of reasonable excuse. However, there may be situations where there are no alternatives which are less detrimental to the scheme.

We will only consider – and will only expect the person to have considered – viable alternatives for the person’s own actions. For instance, a prospective lender to the employer would not be expected to have explored whether a competitor might have lent on less detrimental terms.

We will not expect a person to know more than they should have known at the time of the act, had they made reasonable enquiries.

The extent to which alternatives could have been explored will be context-dependent. The amount of time available to consider alternatives, and the capacity to incur the costs of doing so, may vary. For example:

- In some restructuring situations, events move at pace and decisions need to be made quickly to avoid material destruction of value in a way detrimental to all stakeholders, including the pension scheme creditor.

- We will not expect information to have been sought or analysis conducted where that would not have improved decision-making

We will not use hindsight when considering whether a viable alternative could have avoided or reduced the impact on the scheme. For example, the directors of a distressed employer may identify a number of alternative restructuring proposals, but assessing the relative detriment between those alternatives may involve a judgement as to how events will play out in the future. This could include the success of the employer’s turnaround, whether key customer contracts will be renewed or how the wider economy performs. The directors may not be certain which is the least detrimental option to the scheme. Our assessment of their actions will take account of their knowledge (including their reasonable expectations/forecasts) at the time, had they made reasonable enquiries.

In determining whether an alternative course of action is viable, we will take account of:

- The person’s existing rights

- Their duties or obligations to the scheme, and their duties or obligations to others, and

- The manner in which they reasonably could have exercised their rights.

In considering how parties could have acted in any viable alternative scenario, we will assume that they would not act arbitrarily, capriciously or unreasonably, and that they would act with honesty, good faith, and genuineness.

For example, a potentially viable alternative might involve a sale requiring a third party’s consent. We would assume, subject to evidence demonstrating otherwise, that the third party would have acted rationally in deciding whether or not to grant that consent.

The offences do not enhance the creditor status of the scheme. Therefore, when considering whether the person had a viable alternative, we would not expect the scheme’s interests to be prioritised in a way which would be inconsistent with any statutory duties the person owes.

Examples of scenarios in which it might be considered that there was no less detrimental viable alternative would be where:

- The employer raises debt with prior ranking security to that of the scheme or with a yield that is higher than conventional bank debt, where the new debt is critical for the survival of the business.

- Considering the actions of the directors of the employer, there was no less onerous source of finance available, and continuation of the employer is a better outcome for the scheme than its insolvency.

- Considering the actions of the lender, it was under no obligation to lend, and owed no duties or obligations to the scheme. The lender was entitled to act in the best interests of its shareholders and was not acting unreasonably. We would not seek to argue that a viable alternative was for the lender to lend on uncommercial terms.

- An employer faces a liquidity crisis and approaches its bank to increase the employer’s unsecured facilities and the bank is under no obligation to do so. The bank declines to lend further sums. Having unsuccessfully sought alternative financing, the directors of the employer start insolvency proceedings.

- The bank owed no duties or obligations to the scheme or the employer. It was entitled to act in the best interests of its shareholders and considered that advancing funds to the employer would not be consistent with that. We would not argue that a viable alternative would involve the bank taking an uncommercial decision.

- The directors of the employer balanced the depth of search for alternatives to insolvency with the needs to avoid wrongful trading and preserve what value they could for the benefit of the employer’s creditors. We would not seek to argue that the directors had a viable alternative of refinancing where such lending was not available to them in the market.

A person’s awareness of the potential harm to a scheme will not mean, in and of itself, that the person should have pursued an alternative course of action. In the second example above, although the bank may be well aware that failing to lend more money could result in the insolvency of the employer, we would not expect it to lend if its directors assessed that to do so was against the bank’s commercial interests.

Examples of scenarios where there was a less detrimental viable alternative would be:

- An employer has breached its banking covenants, entitling its lender to withdraw facilities immediately, but an extension of facilities by one month is highly unlikely to risk the lender’s interests because the employer is entitled to significant payments from debtors over that period. The one-month extension is likely to be a viable alternative.

- A parent company and its subsidiary (a DB scheme employer), each owning 50% of another group company, X, sell X to a third party. The entirety of the sale proceeds is remitted to the group treasury company to reduce the group’s debt, with no mitigation provided to the scheme. The employer was dependent on income from X for its viability, and subsequently becomes insolvent. There is no pressing need to reduce the group’s debt - the motivation is to maximise the group’s liquidity ahead of a possible bid for another company, however other sources of finance are available. The viable alternative is that the group could have sourced the funds from elsewhere.

- An employer is facing imminent insolvency, but its directors choose to declare a dividend shortly before appointing administrators. In administration, the scheme receives 20p in the £, as do the other unsecured creditors. The directors have breached their duty to have regard to the interests of the company’s creditors as a whole. There was a viable alternative of not declaring the dividend, which would have been less detrimental to the scheme. However, we would not assert that a viable alternative involved paying the scheme a higher rate of recovery in administration than other unsecured creditors.

The application of our principles-based approach to some common scenarios

There are some common activities and behaviours which, when assessed against the factors set out above, we consider likely to give rise to a reasonable excuse. You can read more about this in appendix 2.

F: Clearance statements and engagement with TPR

Under section 42 of the Pensions Act 2004, a person can apply to us for a clearance statement in relation to our CN power. As outlined in our clearance guidance:

- We expect applications for clearance to only be made by people who could be subject to a CN or a financial support direction.

- Our practice, when granting CN clearance, is to issue a statement under section 42(2)(b) only - that, in our opinion, in the circumstances described in the application it would not be reasonable to impose liability on the applicant under a CN.

Section 42 does not apply to the offences under sections 58A and 58B, and there is no equivalent provision applicable to those offences. Therefore, we cannot issue a clearance statement in relation to the offences.

If we have granted clearance under section 42 in respect of an upcoming transaction, that clearance statement will not automatically mean that the person has a reasonable excuse for the purposes of the offences. However, the addressee of the clearance statement might seek to rely on the mitigation described in their clearance application as part of their basis for saying that they have a reasonable excuse in relation to potential criminal liability. We would consider that mitigation in line with the approach set out in section (E) above.

Should the clearance application contain any false or misleading information, or be incomplete, and that is relevant to the adequacy of any mitigation provided, the mitigation will no longer be regarded as adequate when considering the person’s reasonable excuse in connection with these criminal powers.

G: Selecting cases for investigation and prosecution

Our initial approach

We can become aware of activity of concern in number of ways, such as a Notifiable Event report, a whistleblowing or member complaint, information gained through our intelligence function or reports in the press or other public media.

We will generally carry out an immediate assessment with the aim of reaching an early view on whether our powers may be engaged and whether opening an investigation will be appropriate.

If our assessment concludes that our powers may be engaged, our decision to investigate will be risk-based and will take into account number of relevant factors, such as the impact on the funding level of the scheme, whether the report or information highlights any particular concerning features or behaviour, as well as consideration of our available resources.

Starting an investigation

If we do decide to open an investigation, we typically do not start with a pre-determined action such as prosecution in mind but gather information and establish the facts. In most instances, this will generally start with the use of our regulatory information-gathering powers, such as an information notice issued under section 72 of the Pensions Act 2004.

We will assess the powers and other regulatory tools available to us once we have gathered sufficient information to allow us to consider how to proceed, pursuing our statutory objectives in a risk-based and proportionate manner.

The following factors may indicate that we are more likely to focus our investigation on the potential use of the criminal powers or our financial penalty powers:

- there is serious harm to the scheme and members as a consequence of the act

- the person had extensive involvement or influence in the harm caused

- significant financial gains have been made to the detriment of the scheme

- there has been some other unfairness in the treatment of the scheme

- the trustees, TPR and/or the PPF have been misled or not appropriately informed, or where we are engaged in the matter, there has been a lack of openness and timeliness of communication

Please see our overlapping powers policy for more detail on how we approach decisions about which powers we may pursue when we have a choice between use of regulatory, financial penalty powers and criminal powers.

How we will approach and communicate with subjects of our investigations

When we decide to investigate these offences, we will engage with potential suspects. We cannot foresee circumstances in which it would not be appropriate for us to give a suspect the opportunity to put forward their side of the story before taking a prosecution decision, and we expect those we investigate to explain their actions and their reasons for acting as they did.

We will consider any explanation given to us for a person’s actions, and any information put forward to show that alternatives were explored or that there is no material detriment. We expect their actions and the reasons for them to be well documented, and for the person to put forward suitable and sufficient evidence for their actions. We will generally give more weight to evidence given to us at the time, rather than later on in our investigation.

Where there are grounds to suspect that a criminal offence may have been committed and the person’s answers may be used as evidence in a prosecution, any discussion will be conducted in the form of an interview under caution which complies with the requirements of the relevant Code of Practice issued under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE Code of Practice).

When an investigation is considering a criminal offence from the outset, we will make it clear to suspects that our investigation relates to a possible offence under one or both of these powers when we engage with them and will follow and comply with the relevant PACE Code of Practice and all applicable rules of evidence for criminal cases in any further engagement.

If, during the course of a regulatory investigation, we later become aware that there may be grounds to investigate the person as a suspect in connection with an offence under section 58A or 58B, we will again make that known to the person concerned before we interview them, and will follow and comply with the PACE Code of Practice and all applicable rules of evidence for criminal cases.

If we interview a person as a suspect but later decide not to proceed with a prosecution, we will inform them that we reserve the right to review this position if further evidence comes to light that affects our view of the evidence and the prospects of prosecution.

If any information has previously been obtained using our regulatory information-gathering powers, we will only use evidence that is admissible in criminal proceedings.

Choosing whether to prosecute

We will select cases for prosecution in light of:

- Our policy approach to the new offences – ie whether the conduct amounts to the most serious intentional or reckless conduct that was already within the scope of our CN powers, or would be if the person was connected with the scheme employer

- Our statutory objectives and the outcomes that might be achieved from enforcement action in light of the options that are available to us

- Whether prosecution could deter future acts of the kind and signal to others within the regulatory community that this behaviour will not be tolerated

- Whether the matter satisfies the applicable test(s) for prosecutors[1],which requires an assessment of the evidence and for us to be satisfied that a conviction is likely, on the criminal standard of proof (the ‘evidential test’), and that pursuit of conviction is in the public interest (the ‘public interest test’).

We would only be able to prosecute these offences if the evidence is strong enough to demonstrate that the required legislative tests for the offence are likely to be met to the criminal standard of proof, of beyond reasonable doubt, and that the applicable prosecutor’s test(s) are likely to be met[2]:

- For us to bring a prosecution in England and Wales, we need to be satisfied that the two-stage test in the Code for Crown Prosecutors (the evidential test and public interest test) is likely to be met. The evidential test requires us to be of the opinion that there is sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction against the suspect.

- For a prosecution in Northern Ireland, we would apply the evidential and public interest test in the Code for Prosecutors issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland where that jurisdiction applies.

- The prosecuting authority in Scotland is the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. If we become aware of evidence concerning these offences relating to that jurisdiction we would take a similar approach to that for cases in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. This would involve assessing whether there is sufficient evidence to support referring the matter to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service for it to then make its own independent assessment under the Scottish Prosecution Code as to whether to prosecute any case we referred, based on their view of the evidence and the public interest in prosecuting.

Together this represents a high threshold, so criminal proceedings are reserved for only the most serious types of conduct or behaviour.

Other powers and publications

Our Prosecution Policy provides further guidance on our approach to the investigation and prosecution of criminal offences generally, and our Overlapping powers policy contains information on our approach to situations where we have more than one power available to us.

Our approach to the investigation and prosecution of the criminal offences under sections 58A and 58B does not apply to any of our other powers.

Under s58C and 58D of the Pensions Act 2004, we have the power to issue a financial penalty in respect of conduct which may amount to an offence under section 58A or 58B.

However, if someone has been convicted of or is the subject of ongoing criminal proceedings regarding that conduct, we are prevented under Section 88A(10) from issuing them with a financial penalty.

You can read more about our approach to these financial penalties under section 88A in our Monetary penalties policy.

Footnotes for this section

- [1] In England & Wales: The Code for Crown Prosecutors. In Northern Ireland: The Code for Prosecutors. In Scotland: The Scottish Prosecution Code

- [2] In England & Wales: The Code for Crown Prosecutors. In Northern Ireland: The Code for Prosecutors. In Scotland: The Scottish Prosecution Code

Appendix 1: More detail on the offences - comparison with CNs and the financial penalties in sections 58C and 58D

The offences

Under section 58A(2), someone commits the offence of avoidance of employer debt if they:

- do an act or engage in a course of conduct that:

- prevents the scheme from recovering all or any part of the debt that is due from the employer under section 75 of the Pensions Act 1995

- prevents that debt becoming due

- compromises or otherwise settles that debt, or

- reduces the amount of that debt which would otherwise become due,

- they intended their actions to have this effect, and

- they didn’t have a reasonable excuse for doing the act or engaging in the course of conduct.

The debt under section 75 of the Pensions Act 1995 is a statutory debt owed by the employer to the trustees of the scheme, which becomes payable in circumstances defined by the legislation. These include when the employer suffers an insolvency event, or the scheme is wound up. Section 75 requires the scheme actuary to estimate the amount needed to secure the scheme's liabilities with annuities bought from a regulated insurance company.

Under section 58B(2), someone commits the offence of risking scheme benefits if:

- they act or engage in a course of conduct that detrimentally affects in a material way the likelihood of accrued scheme benefits being received (whether or not the benefits are to be received under the scheme)

- they knew or ought to have known that what they were doing would have that effect, and

- they did not have a reasonable excuse.

In this context, accrued scheme benefits are benefits which were accrued before the act, or before the last act in the series (section 58B(4) and (5)). Please refer to sections 67A(6) and (7) of the Pensions Act 1995 (section 58B(6)), for a definition of what amounts to accrued (or subsisting) rights. Benefits that members receive from the PPF or under the Financial Assistance Scheme are to be disregarded when considering what scheme benefits are accrued (section 58B(7)).

Common elements

The offences under sections 58A and 58B of the Pensions Act 2004 have the following features in common:

- They can only be committed in respect of an occupational pension scheme that is not a money purchase scheme (sections 58A(1) and 58B(1))

- They are committed where:

- someone does or fails to do something within sections 58A(2)(a), 58B(2)(a), 58A(3), or 58B(3), or

- someone aids, abets, counsels or procures (referred to in this guidance as “helps or encourages”) another person to do this

- They didn’t have a reasonable excuse for:

- acting as they did, or

- helping or encouraging someone else to do that act.

- The offences cannot be committed by someone appointed as and acting within their functions as an insolvency practitioner (section 58A(4) and (9) and section 58B(8)).

Our CN power, and points of commonality and difference with the new offences

Under section 38 of the Pensions Act 2004, we can issue a CN to require a person to pay the scheme’s trustees, or the PPF, a specific amount. The new offences have some similar elements to the existing provisions in section 38.

Below, we set out the points of commonality and of difference between the new offences and the provisions of section 38.

Our CN power

We can issue a CN requiring a person to pay a sum to the trustees of a scheme, or the PPF, if:

- the person was at any time in the relevant period

- the scheme’s sponsoring employer or

- connected with, or an associate of, the employer

and

- they were party to an act or a failure to act which satisfies one of the following:

- the main purpose of the act, failure or series, or one of its main purposes was:

- to prevent the recovery of all or part of a debt due to the scheme under section 75 or

- to prevent that debt from becoming due, to compromise or otherwise settle that debt, or to otherwise reduce the amount of debt which would otherwise become due

or

- the act, failure or series detrimentally affected in a material way the likelihood of accrued scheme benefits being received by or in respect of scheme members

or - we are of the opinion that, if a debt to the scheme had fallen due under section 75, the amount of that debt that the scheme would have recovered would have materially reduced as a consequence of the act

or - we are of the opinion that the act reduced the value of the resources of the employer, and that the reduction was material when compared to the amount of the scheme’s estimated section 75 debt

and

- the main purpose of the act, failure or series, or one of its main purposes was:

- we are of the opinion that it is reasonable to impose liability on the person to pay the sum specified in the notice, having regard to

- the extent to which, in the circumstances of the case, it was reasonable for them to act in the way they did, and

- other matters we consider relevant.

Points of commonality between our CN power and the offences

Two of the four bases for use of the power to issue a CN under section 38 are mirrored in the offences in sections 58A and 58B of the Pensions Act 2004, where:

- The act, failure or course of conduct:

- prevented the recovery (in whole or in part) of the employer’s debt to the scheme under section 75

- prevented that debt becoming due

- compromised or otherwise settled that debt or

- reduced the amount of that debt that would otherwise become due (section 58A(2)(a))

or - material detriment has been caused to the likelihood of members receiving their accrued scheme benefits (known as the ‘material detriment’ test) .

Points of difference between our CN power and the offences

However, there are differences between them, on the one hand, the power to issue a CN, and on the other, the offences in sections 58A and 58B, including:

- The power to issue a CN rests with our Determinations Panel, whereas it is the criminal courts which decide whether the offences are proven.

- In the case of the offence under section 58B, it is for the prosecution to prove that the person knew or ought to have known that their actions would cause material detriment to the likelihood of members receiving their benefits. By contrast, in the case of a material detriment CN, should a target wish to establish the statutory defence under section 38B the burden would be on them to show that they gave due consideration to whether or not the intended act or failure to act would cause material detriment, and reasonably concluded that it would not – or that they took all reasonable steps to eliminate or minimise the anticipated material detriment before reaching that conclusion.

- The offences can be committed by anyone other than an insolvency practitioner appointed and acting within the scope of that appointment. Insolvency practitioners appointed and acting within the scope of those appointments are also excluded from the scope of a CN. By contrast, a CN can only be issued to someone who is the employer or was associated with or connected to the employer (as defined in the Insolvency Act 1986) in the period between the act or failure to act and TPR issuing a warning notice.

- The role of reasonableness is different for the CN power and these offences. In order for a CN to be issued, the Determinations Panel must be of the opinion that it is reasonable to impose liability on the person to pay the sum specified in the CN. By contrast, for a prosecution to succeed under either of the offences, the prosecution must prove that the person did not have a reasonable excuse for doing the act or engaging in the course of conduct.

- Like the offence of avoidance of employer debt in section 58A, a CN may be issued where one or more of the main purposes of the act or failure was to prevent the recovery (of the whole or any part) of a debt which was due from the employer under section 75. Unlike the offence, a CN may also be issued where the main purpose of the act or failure was to prevent recovery (of the whole or any part) of a debt that might become due under section 75. The offence in section 58A does not apply where the act or failure prevented the recovery of any part of a debt that had not been triggered at that time (but it does apply where the debt that has been triggered is a contingent debt).

- There is a statutory limitation period applicable to our CN power. We may only issue a CN to someone we issued with a warning notice within six years of the date of their act or failure. There is no limitation period applicable to the criminal powers in sections 58A and 58B.

Points expressed differently, but which we regard as the same in substance

There are also instances where sections 58A and 58B are drafted in a different way to section 38, but we take the view that the intention was to achieve the same effect. These occur when:

- The offences are committed by a person who “does an act or engages in a course of conduct”. Anyone who helps or encourages the commission of either of the offences (see section 8 of the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861) or agrees with another to commit the offences (see section 1 of the Criminal Law Act 1977) is also criminally liable. A CN can be issued to someone who “was party to an act or deliberate failure to act”, and the parties to an act include those who “knowingly assist in the act or failure”.

- The offence under section 58A is committed by someone who “intended” their act or course of conduct to have the effect of avoiding the employer’s section 75 debt. A CN can be issued to someone where “the main purpose or one of the main purposes” of their act or deliberate failure to act was avoiding the section 75 debt.

We interpret these provisions of section 58A/58B and section 38 in the same way.

Our financial penalty powers, and points of commonality and difference with the new offences

Financial penalties for avoidance of employer debt and conduct risking accrued scheme benefits

Sections 58C and 58D of the Pensions Act 2004 give us the power to issue a financial penalty for ‘avoidance of employer debt’ and for ‘conduct risking accrued scheme benefits’.

Those sections enable us to issue a financial penalty to require a person to pay a sum of up to £1m where they have been a party to an act which, in the case of section 58C (‘avoidance of employer debt’), had a main purpose which was:

- to prevent the recovery of all or part of a debt due to the scheme under section 75 or

- to prevent that debt from becoming due, to compromise or otherwise settle that debt, or to otherwise reduce the amount of debt which would otherwise become due

or, in the case of section 58D (‘conduct risking accrued scheme benefits’), detrimentally affected in a material way the likelihood of accrued scheme benefits being received by or in respect of scheme members.

We may only issue a penalty under either of those sections where the person acted with the requisite purpose (section 58C) or knowledge (section 58D), both of which are discussed further below, and if it was not reasonable for the person to act in the way that they did.

There are some points of commonality and of difference between the new offences in sections 58A and 58B and the financial penalties in sections 58C and 58D.

Points of commonality between the financial penalties and the offences

We regard the ‘act’ part of:

- the penalty power under section 58C as the same in scope as the ‘act element’ of the offence under section 58A , and

- the penalty power under section 58D as the same in scope as the ‘act element’ of the offence under section 58B.

There is no financial penalty power based on the new CN ‘act’ tests of the ‘employer insolvency’ and ‘employer resources’ tests.

The ‘mental element’:

- We regard the ‘mental element’ of the section 58C penalty as the same in substance to that of the offence in section 58A – but the legislation expresses this differently, as is described below.

- In the case of the section 58D penalty, we would need to show that the person ‘knew or ought to have known’ that their act would have that effect. This is the same as the ‘mental element’ for the section 58B offence.

Liability under the offences under sections 58A and 58B, and the financial penalties under sections 58C and 58D, can be imposed on any person except for a person acting in accordance with their functions as an insolvency practitioner.

There is no statutory limitation period applicable to our financial penalty powers in sections 58C and 58D, or to the criminal powers in sections 58A and 58B.

Points of difference between the financial penalties and the offences

However, there are differences between, on the one hand, the power to issue a penalty under either section 58C or 58D, and on the other, the offences in sections 58A and 58B, including:

- The power to issue a financial penalty under either or both of sections 58C and 58D rests with our Determinations Panel, whereas it is the criminal courts which have jurisdiction for the offences in sections 58A and 58B and will decide whether the offences are proven.

- The standard of proof is different. For the criminal offences, the prosecuting authority must prove the elements of the offence ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. The elements of the financial penalties must be proved ‘on the balance of probabilities’.

Points expressed differently, but which we regard as the same in substance

There are also instances where sections 58A and 58B are drafted in a different way to sections 58C and 58D, but we take the view they have the same effect.

- In order for a financial penalty to be issued under section 58C or 58D, the Determinations Panel must be of the opinion that it was not reasonable for the person to act or fail to act as they did. For a prosecution to succeed under either of the offences, the prosecution must prove that the person did not have a reasonable excuse for doing the act or engaging in the course of conduct. We regard these as the same in substance (although the standard of proof is different – as described above).

- In the case of the section 58C penalty, we would need to show that the person’s main purpose, or one of the person’s main purposes, for acting as they did was to have the prescribed effect on the employer debt. The offence under section 58A is committed by someone who “intended” their act or course of conduct to have the effect of avoiding the employer's section 75 debt. Although the legislative provisions are drafted differently, we interpret these provisions as meaning the same thing.

Footnotes for this section

- [3] There are additional grounds for issuing a CN, namely the employer insolvency test set out in section 38C of the Pensions Act 2004 and the employer resources test set out in section 38E. There is no equivalent criminal liability in respect of these tests.

- [4] We do not regard either the offence in section 58A nor the financial penalty in section 58C as applying where the act or failure prevented the recovery of any part of a debt that had not been triggered at that time (ie neither applies to a debt that “might become due”), although each applies where the debt that has been triggered is a contingent debt.

Appendix 2: Our approach to some common behaviours and activities

Section (E) of the body of this policy sets out the principles which we will apply when considering whether a person has a reasonable excuse. The application of those principles will depend on the particular actions which a person takes and the wider factual context.

This appendix sets out how we generally expect the principles to apply in a number of common situations. In each of the situations set out below, we would generally expect a person to have a reasonable excuse for their activity in relation to the offences under sections 58A and 58B (subject, where applicable, to the conditions noted below).

Statutory defence to material detriment

Where a person is able to establish a statutory defence to a material detriment CN under section 38B of the Pensions Act 2004.

Multi-employer schemes and debt management arrangements provided by legislation

Where a person enters into an easement under the Occupational Pension Schemes (Employer Debt) Regulations 2005, provided that:

- the applicable legislative conditions have been complied with

- in the case of scheme trustees, they acted in good faith in accordance with their fiduciary duties, and

- in the case of any (existing or new) employer to the scheme, they have been transparent with all parties involved about the context in which the easement is being used

There are various easements and mechanisms for managing debts and liabilities that arise in the context of multi-employer schemes provided for in the Occupational Pension Schemes (Employer Debt) Regulations 2005. The conditions to use these arrangements involve the agreement of at least the trustees and an employer to the scheme, and in many instances the agreement of other parties.

Circumstances which we consider would not normally meet any of the material detriment, employer insolvency or employer resources ‘act’ tests for CNs in our code-related guidance

Where the person’s actions fall exclusively within the examples of activities which would not normally be materially detrimental to the likelihood of members receiving their accrued benefits, or meet the employer insolvency or the employer resources tests, as set out in the code-related guidance accompanying Code of Practice 12 (Circumstances in relation to the material detriment test, the employer insolvency test and the employer resources test).

Some restructuring mechanics

Where a person proposes, or acts in accordance with, a scheme authorised by a court under Part 26A of the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020, provided that:

- the scheme is compliant with the legislative conditions, and

- relevant information has been shared with us, the trustees and the PPF.

Where a person proposes, or acts in accordance with, a company voluntary arrangement (CVA), provided that:

- the scheme’s creditor interest has been fairly valued

- the scheme (via the PPF) had the opportunity to vote in the CVA, and

- relevant information has been shared with the trustees and the PPF

Advisers

Where an adviser has acted in accordance with their professional duties, conduct obligations and ethical standards applicable to the type of the advice being given.

The applicable duties, obligations and standards will ordinarily depend on the professional discipline and oversight by the appropriate regulatory body.

We may consider prosecution of advisers in the following scenarios where the conduct they helped or encouraged meets the ‘act’ test for the offence of conduct risking accrued scheme benefits:

- A legal adviser who helps an employer to lay a trail of false evidence designed to hide the employer’s true intention for their actions and / or form the basis for a reasonable excuse defence.

- An investment manager who encourages a scheme to change their current appropriate investment strategy to one that significantly increases downside risk with little corresponding upside in order to earn a performance fee. This change results in a higher level of risk to the likelihood of members receiving accrued scheme benefits.

- An actuary engaged by the employer who provides accountancy advice on whether the funding test for a flexible apportionment arrangement is met, knowing that they don’t have the requisite expertise to provide such advice and that their regulatory body does not regulate the giving of such advice. They also expect the scheme trustees to rely on it, when there is high probability that the replacement employer could not support the scheme in the way the test examines, thereby reducing the likelihood of members receiving full benefits.

- An accountant who knowingly assists in a material misstatement of the employer’s accounts in the knowledge these will be relied on to support a going concern status in an upcoming sales process which caused material detriment.

Appendix 3: Illustrative case study

This case study applies the principles set out in the above policy to a fictional scenario. It only examines the application of the criminal offences under sections 58A and 58B of the Pensions Act 2004, and does not address how we might choose between a number of potentially overlapping powers.

A real transaction might involve facts which are considerably more detailed than those in this case study. You should refer to the main body of the policy when considering the application of the offences to your own circumstances.

Background

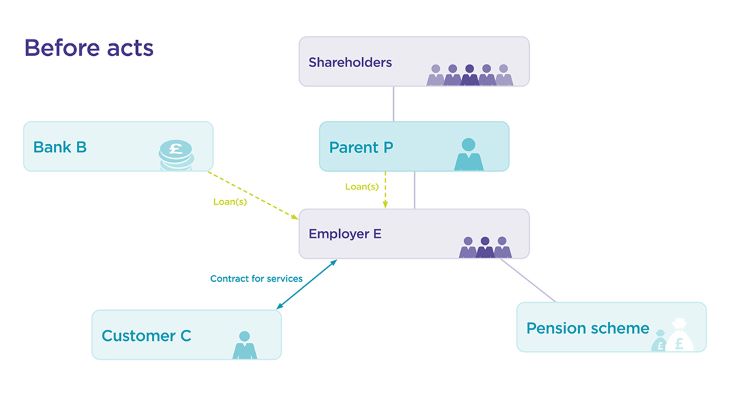

Employer E, based in Brighton, is the sole employer of a DB scheme which has a significant s75 deficit (and a substantial deficit on the scheme’s Part 3 basis).

Employer E’s business is reliant on long-term contracts with a small number of customers in a declining industry, and is profitable. There is very little potential to win new customer contracts.

Bank B provides term loan and overdraft facilities to E, the balances of which are secured on E’s assets.

E is owned by Parent P. P has made a number of loans to E in recent years in order to provide working capital. Those loans are unsecured and are repayable on demand (ie they can be deemed due and payable at a time of Parent P’s choosing). No dividends have been paid by E to P for the last three years and, as a result, P has been unable to make any distributions to its shareholders.

Employer E has been told that its biggest customer, C, has selected a competitor of Employer E as the frontrunner in relation to the retendering of its contract with Employer E. Employer E is therefore likely, but not certain, to lose C’s business in the near-term. If Customer C does not renew its contract, Employer E will need to secure new business of a similar value to avoid insolvency in the near-term.

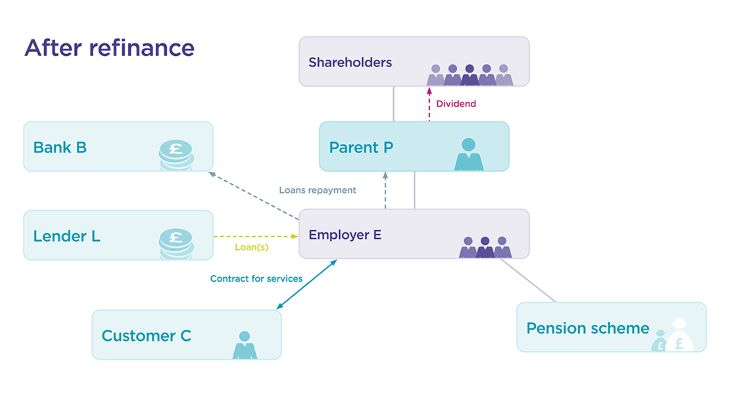

Parent P wishes to pay a dividend to its shareholders. In order to do so, it requires funds from E and demands repayment of the loans. P is fully aware that Employer E expects to lose its most significant supply contract with Customer C, and if it does so, that it would likely become insolvent in the near-term and then Parent P would be unlikely to recover its loans in full.

E has insufficient headroom within its existing banking facilities to make the repayment. Employer E raises concerns with Parent P about repaying Parent P given the prospect of losing Customer C and the likelihood of insolvency thereafter. However, Parent P insists on repayment, and threatens to replace the directors of Employer E if Parent P is not repaid in short order. Parent P instructs E to increase its external lending facilities or alternatively to find another source of funding to enable E to repay the loans to P.

Employer E requests an extension of facilities from Bank B. Bank B declines to extend the facilities as it is concerned that the extended facilities may not be fully secured in the event of an insolvency.

Employer E approaches Lender L. L is prepared to provide the larger replacement facilities, albeit at a materially higher interest rate than that charged by Bank B, subject to its lending being fully-secured by way of fixed and floating charge security over all of E’s assets. An offer to lend, subject to confirmatory due diligence, is made.

As part of L’s due diligence on Employer E, E presents business plans for the next three years. These business plans anticipate that the extra lending is used for working capital, and are based on an assumption that each of the customer contracts that come up for renewal in that period are renewed. Employer E does not tell Lender L that it expects to lose its most significant customer, C, but L has in any event assessed its exposure if a contract is lost – and L knows that in such an event it would make a full recovery due to the extent of its security.

At the same time, Employer E engages with the trustees of its DB scheme about the proposed refinancing. Employer E tells the trustees that the extra funds will be used to grow the business. The trustees are concerned that the increased level of borrowing, together with the materially higher interest rate, could be detrimental. E doesn’t inform the trustees of the possible loss of the contract with C, or the intended dividend to P. The trustees request mitigation, but that is refused.

E refinances with L and immediately uses the majority of the extra funds (after repayment of Bank B) to repay the loans from P. P uses the loan repayment to fund a dividend to its shareholders.

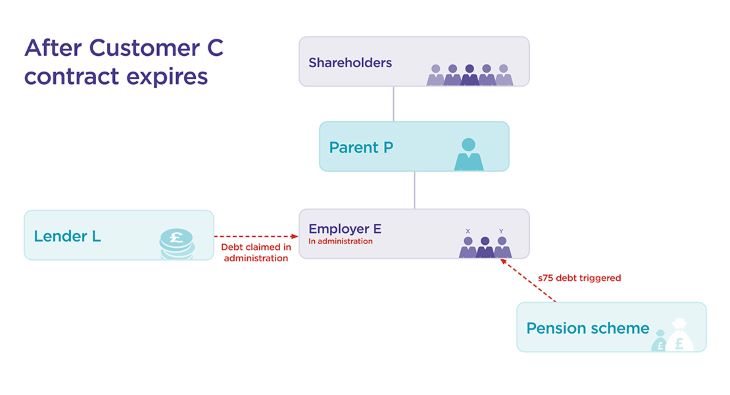

C does not renew its contract. As a result, E is unable to meet the repayments under the facilities with L.

L appoints administrators, and then submits a proof of claim for the entirety of the outstanding debt, its fees and the interest which had accrued. The administrators sell E’s assets to a third party (which has no connection to any of the parties identified above) for fair value.

L recovers all of its claim. The trustees, and E’s other unsecured creditors, recover only a few pence for every pound of debt they claim. The scheme has a substantial PPF deficit, and is expected to be assumed by the PPF, with members’ benefits capped at PPF levels.

General consideration of the offences

For a person to be successfully prosecuted under section 58A or 58B, TPR would need to show that:

- there is sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction, and

- prosecution is required in the public interest.

The majority of the acts in this case study precede the appointment of administrators, and therefore took place when no section 75 debt had been triggered. This means that we could only consider the possibility of prosecution under section 58B in relation to those activities.

However, one act took place when the section 75 debt had been triggered – Lender L’s decision to claim its debt, fees and accrued interest – so prosecution in relation to that act could be considered under section 58A.

For the purposes of this case study, we consider the prospects for prosecution in relation to each of the ‘actors’ involved in the scenario, analysing all of the applicable limbs of the relevant tests. We will assess the acts firstly in relation to section 58B, and then the one act that could engage section 58A.

In an actual case, our approach may differ in that we may choose not to undertake a detailed consideration of the merits of prosecuting one or more of the ‘actors’, or may first consider reasonable excuse without first assessing the ‘act’ and ‘mental’ elements.

Neither section 58A nor 58B would apply to the actions of the administrators in this case study[5] .

Assessing the facts in relation to the offence in section 58B

If we were considering prosecution under section 58B, we would consider whether there is sufficient evidence that:

- the ‘act element’ is met – ie that the person did an act or engaged in a course of conduct that detrimentally affected in a material way the likelihood of accrued scheme benefits being received

- the ‘mental element’ is met – ie that the person knew or ought to have known that their act would have a materially detrimental effect

- the person did not have a reasonable excuse

each to the criminal standard of ‘beyond reasonable doubt’, and that

- prosecution is required in the public interest.

The ‘actors’ considered in relation to possible prosecution under section 58B are:

- Employer E

- Parent P

- Bank B

- Lender L

- Customer C

Employer E

The key actions of Employer E were:

- It refinanced, creating increased secured borrowing at a higher interest rate than was the case for its facilities with Bank B.

- It repaid the loans to Parent P.

The ‘act element’:

- We assess acts (1) and (2) as a course of conduct. Based on a detailed assessment of the facts, we come to the conclusion that this course of conduct meets the ‘act element’.

The ‘mental element’ in relation to the course of conduct:

- Employer E was aware that Customer C was unlikely to renew its contract, and that this in turn was likely to bring about its insolvency. It similarly knew that taking out more borrowing and repaying the loans to Parent P would substantially reduce the outcome for its unsecured creditors, including the scheme (Employer E’s largest unsecured creditor by some margin), in any insolvency proceedings. The evidence indicates that Employer E was motivated so as to comply with Parent P’s instructions. We come to the conclusion that the ‘mental element’ is met in relation the course of conduct.

Considering whether E had a reasonable excuse:

- Focusing initially on the three ‘factors of significance’ set out in the policy:

- Was the detrimental impact an incidental or central part of Employer E’s purpose? Employer E acted so as to pre-empt its insolvency and bypass the insolvency distribution process. Employer E’s purpose was to ensure that its parent company and its ultimate shareholders benefited from full repayment of Parent P’s loans, knowing that such repayment would likely be at the expense of other unsecured creditors, including the scheme. The detrimental impact to the scheme was central to Employer E’s purpose in favouring Parent P.

- Was adequate and timely mitigation provided? No mitigation was provided, so the next factor is engaged.

- Was there a viable alternative course of action for Employer E which would have resulted in less detriment for the scheme? Yes, Employer E did not have to take out the additional borrowing, and nor should it have repaid Parent P given that it knew its insolvency was likely to occur in short order. In formulating this alternative course of action, we take account of the fact that Employer E owed obligations to all of its creditors, and its directors may well have owed statutory duties to those creditors to act in their best interests. Employer E should not have favoured Parent P over the others, and Employer E acted unreasonably, with an absence of honesty, good faith and genuineness.

- We would also consider all other relevant factors and, in particular, Employer E’s lack of openness with the trustees weighs against it having a reasonable excuse.

- We conclude that Employer E’s excuse was not reasonable.

We would consider whether the prosecution of E is required in the public interest. The questions in paragraph 4.14 of the Code for Crown Prosecutors, examining seriousness, culpability, harm, impact and proportionality, would indicate that it is.

- We would expect to prosecute Employer E under section 58B.

Parent P

The key actions of Parent P were:

- Instructing and coercing Employer E to repay its loans.

- As part of this, Parent P instructed Employer E to extend its lending facilities or find an alternative source of funding to enable E to repay the loans to P.

The ‘act element’:

- We assess acts (1) and (2) as a course of conduct. Based on a detailed assessment of the facts, we come to the conclusion that this course of conduct meets the ‘act element’.

The ‘mental element’ in relation to the course of conduct:

- Parent P was aware that Employer E did not have the funds to pay back the loans to Parent P. Furthermore, Parent P knew that Customer C was unlikely to renew its contract with Employer E, and that this was likely to bring about the insolvency of Employer E in the near-term. It similarly knew that taking out more borrowing and repaying Parent P’s loans would substantially reduce the outcome for the scheme in any insolvency proceedings. We come to the conclusion that the ‘mental element’ is met in relation the course of conduct.

Considering whether P had a reasonable excuse:

- Focussing initially on the three ‘factors of significance’ set out in the policy:

- Was the detrimental impact an incidental or central part of Parent P’s purpose? Parent P wanted to ensure that it was repaid before Employer E became insolvent, because it knew that its recovery would be significantly reduced on insolvency when any sums available for unsecured creditors would be shared pro rata between them, which would include the scheme. In the context of likely insolvency, its purpose in seeking full repayment had the consequential effect of detriment to unsecured creditors, including the scheme. The proximity of Parent P to the scheme means that we regard the detrimental impact to the scheme as central to Parent P’s purpose.

- Was adequate and timely mitigation provided? No mitigation was provided, so the next factor is engaged.

- Was there a viable alternative course of action for Parent P which would have resulted in less detriment for the scheme? Yes, Parent P did not have to demand repayment of its loans to Employer E, or instruct Employer E to take out the additional borrowing. While Parent P had a contractual right to seek repayment of its loans, we take account of the fact that Parent P exercised its rights at a time when it was aware of the likely impending insolvency of Employer E, and so it acted unreasonably in seeking full payment as a means of avoiding its likely reduced recovery on Employer E’s insolvency.

- We would also consider all other relevant factors, in particular Parent P’s involvement in Employer E’s affairs, which weighs against it having a reasonable excuse.

- We conclude that Parent P’s excuse was not reasonable.

Having considered the tests in 58B are met, we examine whether prosecution of Parent P is in the public interest.

- In light of the factors in paragraph 4.14 of the Code for Crown Prosecutors we conclude that it is, and we pursue prosecution of Parent P.

Bank B

Bank B declined to advance larger facilities.

The ‘act element’:

- Bank B’s act was to refuse to advance further lending to E. Given the facts of this case (including the purpose of the extra lending), the failure to lend did not cause any detriment to the scheme. It was the use of the borrowed funds from Lender L (i.e. the dividend paid to Parent P), and the higher costs of borrowing from Lender L that caused the detriment.

The tests in section 58B cannot be met, so the ‘mental element’ and B’s reasonable excuse are not considered. The evidential test in the Code for Crown Prosecutors is not made out, so we do not consider the public interest test. We do not pursue prosecution of Bank B.

As noted above, in an actual case, we may not necessarily consider the elements of the offence in the order set out above. We could, for example, decide to initially consider whether Bank B had a reasonable excuse for acting, or failing to act, as it did, and only go on to consider whether the ‘act’ and ‘mental’ elements are met if we consider that Bank B did not have a reasonable excuse.

On these facts, we would consider that Bank B did have a reasonable excuse. Consistent with the analysis of the body of this Policy, we do not consider that Bank B had a less detrimental viable alternative – it was entitled to assess its commercial interests and decide not to lend further sums.

Lender L

Lender L did various acts:

- It charged costs on its lending, and those costs were higher than the costs charged by Bank B for its lending. These higher costs were detrimental to other creditors of Employer E, including the scheme.

- It called in administrators when E defaulted on its repayments – if it had not done so, the scheme may have received some limited deficit repair contributions in the intervening period, however the directors of Employer E or another of its creditors would have been expected to bring about Employer E’s insolvency within a short period of time.

- It claimed the entirety of the facilities, fees and the accrued interest – if it had not done so, more funds would have been available for distribution to unsecured creditors including the scheme.

The ‘act element’:

- Based on a detailed assessment of the facts, we come to the conclusion that act (3) meets the ‘act element’.

- The sums paid to Lender L by way of higher charges than Lender B as a result of act (1), and the deficit repair contributions which may have been lost as a result of act (2) are not considered material enough to meet the ‘act element’.

The ‘mental element’ in relation to act (3):

- Lender L was well aware that claiming the entirety of the debt, fees and accrued interest would lead to the scheme receiving next to nothing in the administration of Employer E, and was aware of the materiality of its doing so to other creditors including the scheme. The ‘mental element’ is met in relation to act (3).

- Considering whether L had a reasonable excuse for doing act (3), and focusing on the three ‘factors of significance’ set out in the policy:

- Whilst L was aware of the impact on the scheme, its objective was to protect its existing interests. This had the consequential effect of detriment to unsecured creditors, including the scheme, but Lender L’s lack of proximity to the scheme means that we do not regard this consequential effect as central to Lender L’s purpose. The harm to the scheme was incidental.

- Lender L provided no mitigation to offset the detriment to the scheme, so factor three would be engaged.

- We consider that there were no viable alternatives that were less detrimental, because Lender L had a right to pursue its existing interests in the administration. Employer E had freely agreed to borrow on the terms proposed by L, and L didn’t owe duties or obligations to the scheme or Employer E. Lender L’s directors owed duties to act in the best interests of Lender L’s shareholders, and so acted in pursuit of profit and protection of its exposure. In negotiating the terms of its lending, Lender L did not act arbitrarily, and there was no evidence of any lack of honesty or good faith.

We conclude that Lender L’s excuse was reasonable.

- Having concluded that there is insufficient evidence that the tests in section 58B are met, we do not consider the public interest test in the Code for Crown Prosecutors, and we do not pursue prosecution of Lender L.

Customer C

Customer C chose not to renew its contract with Employer E.

The ‘act element’:

- Employer E was reliant on the contract with Customer C for a substantial part of its income. Based on a detailed assessment of the facts, we come to the conclusion that the decision not to renew meets the ‘act element’.

The ‘mental element’:

- There were a limited number of participants in Customer C’s industry, so Customer C knew that the non-renewal would have a significant effect on Employer E. Because of the long-term nature of its contracts, Customer C conducts some financial due diligence on its suppliers, and so C was aware of the likely impact on the scheme if the contract was not renewed. However, C did not know (and could not have been expected to have known) about the extent of the scheme’s reliance on Employer E. The ‘mental element’ was not met.

The tests in section 58B cannot be met, so C’s reasonable excuse is not considered, and nor is consideration given to whether it would be in the public interest to prosecute C. We do not pursue prosecution.

Assessing the facts in relation to the offence in section 58A

If we were considering prosecution under section 58A, we would consider whether there is sufficient evidence that:

- the ‘act element’ is met – ie that the person does an act or engages in a course of conduct that prevented the scheme from recovering all or any part of a s75 debt, or prevented that debt becoming due, or compromised or settled that debt, or reduced the amount of the debt which would otherwise have become due,

- the ‘mental element’ is met – ie that the person intended their act to have the relevant effect,

- the person did not have a reasonable excuse,

each to the criminal standard of ‘beyond reasonable doubt’, and that

- Prosecution is required in the public interest.

As noted above, the only ‘actor’ identified in the case study who took action after the section 75 debt had been triggered was Lender L, in making its claim in Employer E’s administration.

The ‘act element’: